By Madeleine Klebanoff O’Brien

Last summer I conducted independent research at Houghton Library through Harvard’s remote Summer Humanities and Arts Research Program undergraduate fellowship. Inspired by Houghton’s collections, I created an allegorical map of Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy.

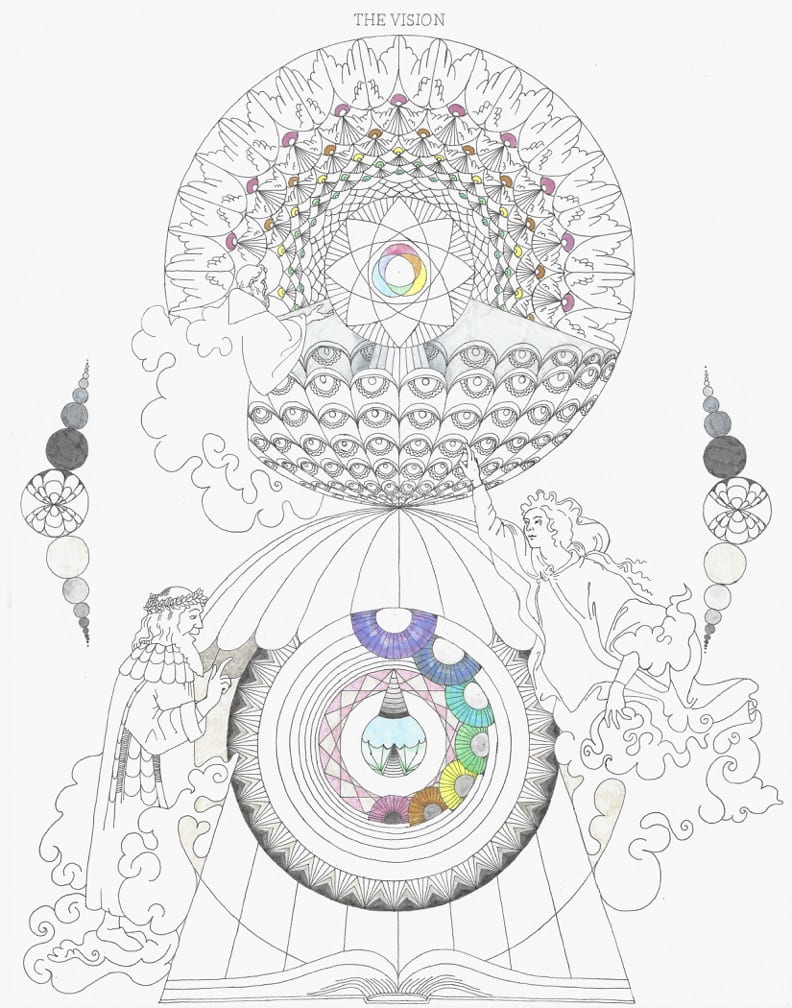

The Comedy follows Dante through Hell, Purgatory and Heaven. It is a cosmography, a “total vision” of the cosmos. While most Comedy illustrations are episodic or focused on infernal topography, my map spans the entirety of Dante’s cosmos. It embodies a “total vision.”

The ultimate “total vision” is the beatific vision, in which Dante sees “by love in a single volume bound, / the pages scattered throughout the universe” (Alighieri, Dante. Paradiso. Translated by Robert and Jean Hollander, Anchor, 2007. XXXIII, 86-87). My map binds, in a “single volume,” the pages of the Comedy. It promises us a glimmer of Dante’s beatitude.

Since beatific light “shines brightest in what resembles it” (Paradiso VII, 75), cosmographical maps lend a double meaning to the term “illuminated manuscript.”

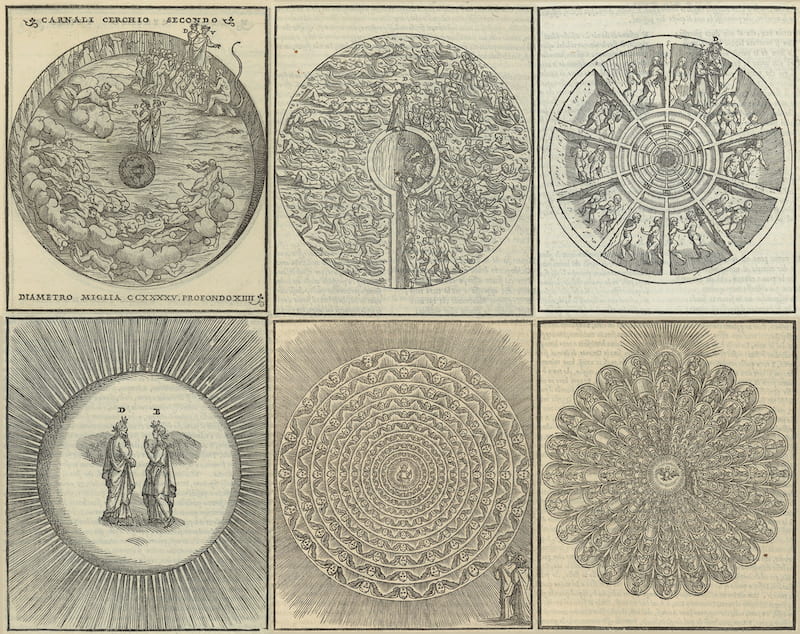

My map emerged from weeks of archival research. I was drawn to Houghton’s Dante collection by an extensively illustrated 1544 edition of the Comedy, but my search quickly expanded beyond Comedy illustrations to include scientific treatises, Renaissance cosmographies and illuminated Bibles. Guided by secondary sources, I followed the visual tradition that shaped and was shaped by the Comedy.

The remote format of the fellowship freed my gaze from logistical constraints. In a digital space, I could shuffle materials like an array of puzzle pieces, searching for unforeseeable compatibilities. Since research resembled creative play, the transition from screen to sketchpad was seamless.

Once I had accumulated an array of sources, I picked up the sketchpad. There, my pencil could cross borders of time, place and discipline to build a “total vision” that was uniquely my own.

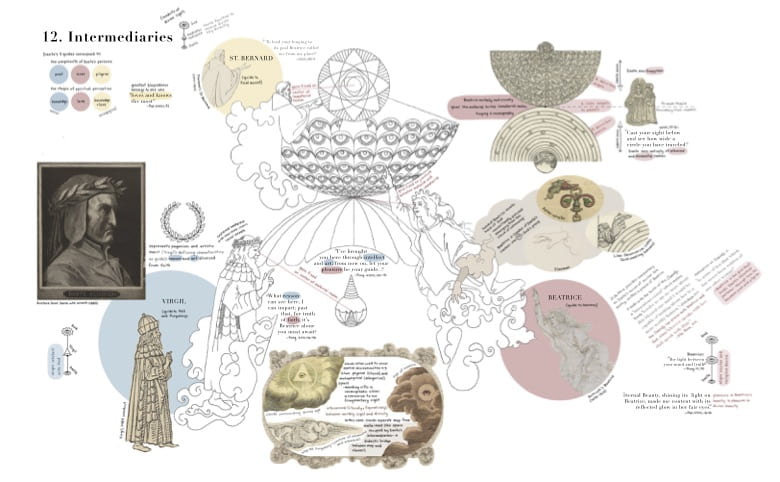

I paired my map with a set of artist’s notes that mirror the pages of my sketchpad. They expose, beneath each region of the map, a web of visual and conceptual associations. If the map is the thesis statement, the notes are the essay body. They forge an argument from images rather than words, harnessing the artistic process to do scholarly work.

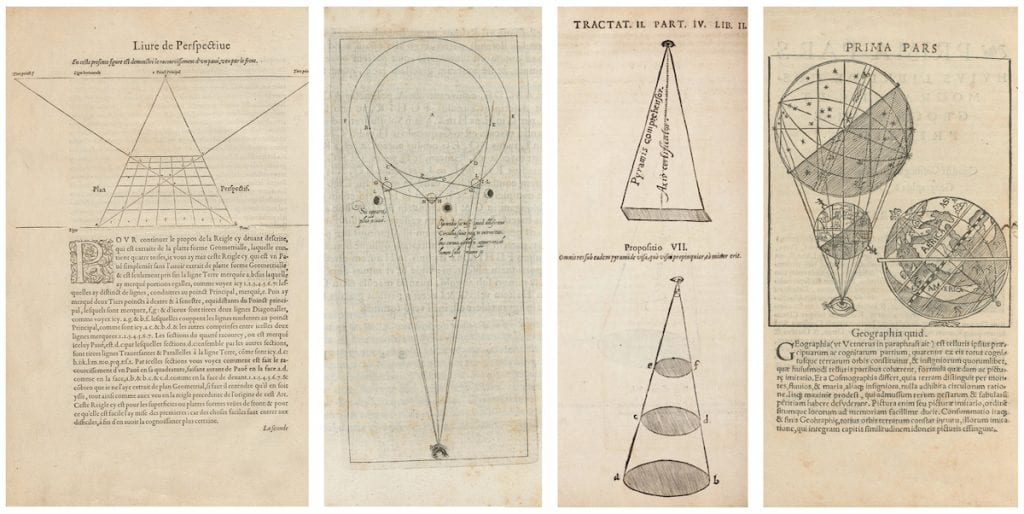

As I sketched, images coalesced around the nucleus of Dante’s poem, drawn by unexpected visual resonances. A triangular perspectival grid, for instance, merged with a triangular “optical cone” so that when I looked at a 1540 diagram of the cosmos as an optical projection, the divine eye became a vanishing point.

Visual likeness led to conceptual likeness. The vanishing point is where parallel lines converge, violating the laws of Euclidean geometry. God is where all things converge, violating human reason. Dante describes this violation in geometric terms. Faced with beatitude, he is “like the geometer who fully applies himself / to square the circle and, for all his thought, / cannot discover the principle he lacks” (Paradiso XXXIII, 133-5).

The map’s primary structure consists of two circles. These represent the immaterial and material heavens, glued along their boundaries to produce a hypersphere. The hypersphere has two centers: Satan, the physical center, and God, the spiritual center. Satan’s gravity tugs the flesh, God’s light tugs the spirit. I therefore arranged the concentric spheres of both heavens according to the inverse square law, which governs the propagation of light and gravity.

I call the secondary, triangular structure of the map the “meta-map.” It describes the map’s transmission, from the divine vanishing point to the pages of the Comedy. You, the viewer, stand at the threshold of the text, ready to embark on a vicarious pilgrimage. Dante’s guides await, flanking the perspectival triangle according to their distance from your mortal sight.

This fellowship taught me the power of visual thought. My eye often outpaced my mind, making connections beyond its scope. I am eager to apply this summer’s methods to future research projects, testing the bounds of visual thought. I encourage others to do the same: to approach scholarship with an artist’s eye.

Madeleine Klebanoff O’Brien is a rising junior studying Comparative Literature at Harvard College. She is currently on leave in Ottawa, Canada.

The Summer Humanities and Arts Research Program (SHARP) is open to all undergraduates at Harvard. The 2021 application deadline is Thursday, February 18. Visit the Harvard College Office of Undergraduate Research and Fellowships (URAF) Summer Residential Research Projects page for more information and to apply.