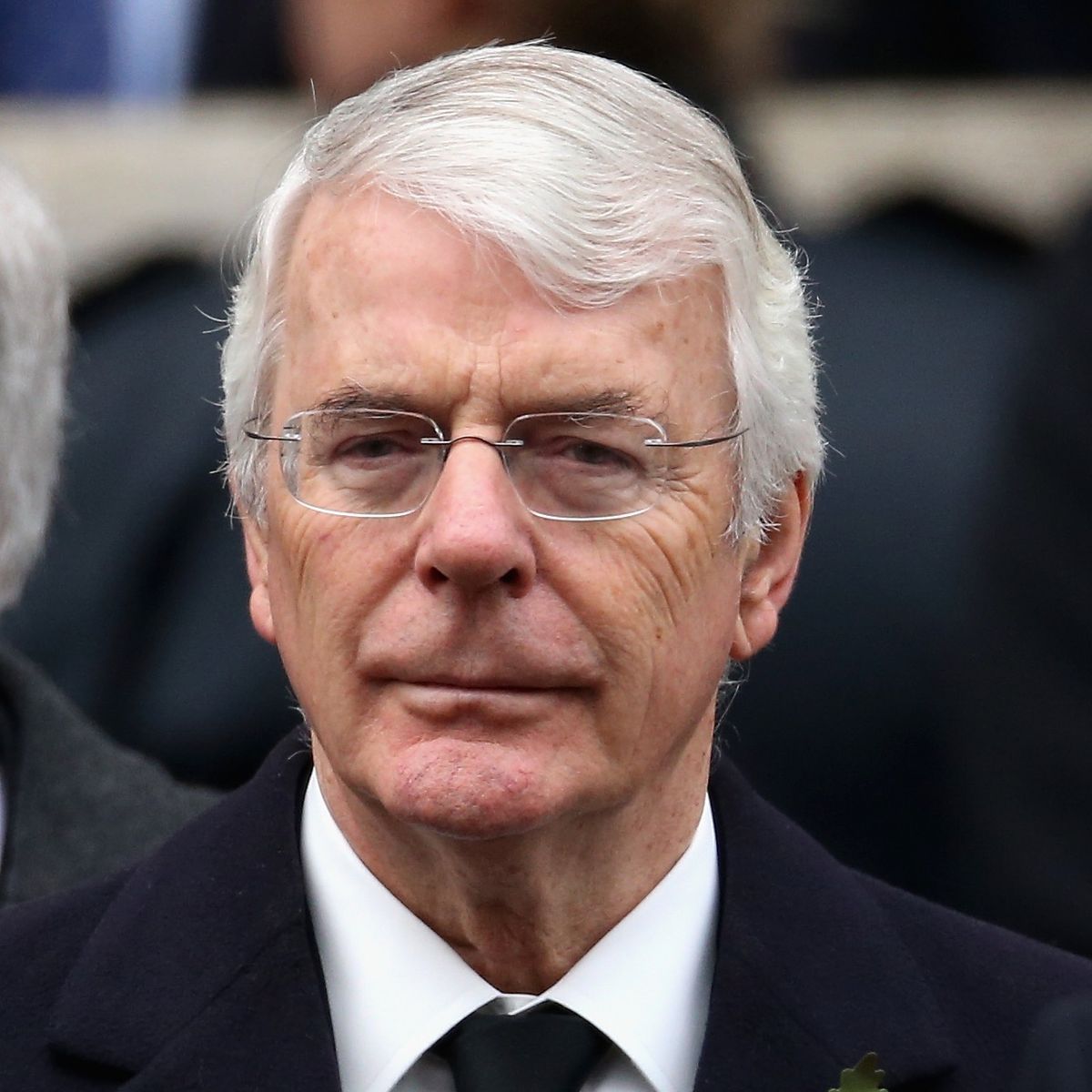

Sir John Major was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1990 to 1997, overseeing Britain’s longest period of continuous economic growth and the beginning of the Northern Ireland Peace Process. Previously he served in the Cabinet as Chief Secretary to the Treasury in 1987. He was promoted to Foreign Secretary in 1989, and then became Chancellor of the Exchequer.

This interview was conducted on 10 May 2022.

Q: Could you set out your role in regional and growth policy over the past few decades?

My role was largely indirect rather than direct. I emphasise that because I never served in the Board of Trade or the Department of Trade and Industry. But I had other roles and, particularly as Chief Secretary, Chancellor and Prime Minister, I had a very distinct role. But it was often secondary, rather than primary, approving policy rather than initiating policy in most cases.

Q: How would you assess the impact of regional and local economic policy over that period?

The record suggests that the success of growth and regional policy over the decades is pretty patchy. If it had been as successful as we would have hoped, we wouldn’t have so many communities left behind. If it had been successful, we would have been able to better resurrect areas where a dominant form of employment collapsed. I have in mind industries such as coal and shipbuilding. And if it had been successful, I’m not at all sure that you would have had this inquiry.

Despite the best efforts of governments plural over 50 years, we have unforgivable regional inequalities – as bad in the UK as anywhere in mainstream Europe; in fact, even among some of the poorer nations of Europe. So I don’t think we can say it was a success.

It wasn’t through indifference. I think it’s more that there was too narrow a focus on attracting investments by governments. Obviously, that is crucial. But for that to lead to successful regional policy, it needs back-up policies to go with it. I have in mind housing to encourage mobility, education to encourage skills, infrastructure to encourage productivity. All of those seem to me to be relevant to what we’re talking about. And of course – I say it simply as a matter of record – it also needs appropriate macro policies. By that I include tax levels, spending levels, inflation, employment and the continuation of growth. Both growth and regional policy are bound to be linked to the overall success of the economy. It’s the old chicken and egg question. Does a successful economic policy boost regional policy, or does regional policy create a successful economy? In fact you need both. Which way around, I’ve never been sure.

The other point about the overall assessment of policy are the areas that I think might have harmed it over the past 50 years. In that list I would include political fault lines. I have in mind policies changing with a change of government for philosophical reasons. I have in mind political disputes. I’m certainly thinking of policy folly like Brexit and the growth of nationalism rather than an adherence to internationalism. It seems to me, if you move towards nationalism, Britain First, America First, call it what you will, you’re going to damage growth in the medium and long term, if not in the short term as well.

The other consideration to include in this introductory thought is that policy is undermined by disunity across the United Kingdom. Disunity isn’t only political. It can be economic as well. It’s also affected by the loss, more recently, of EU structural funds, from which we benefited dramatically for the best part of 40 years. At one stage, we received around 25 to 30 per cent of the regional funds disbursed for the whole of Europe. And the impact was huge.

Q: In political and policy discussions in the early part of the 1980s, to what extent was there an interest in the regional and local impact of policy – what was the philosophy at the time?

When I spoke of political fault lines and policies changing with the change in government, we did move in the 1960s and 1970s between governments that had a very strong view in favour of nationalisation, and national central direction, and then a party that disliked that, and wished to end it as speedily as they possibly could, would move on towards more free market policies.

The reality is that you need a mix. It’s imperative that you have government action, government intervention in many cases, government support where it’s necessary. But it’s also important that you open up structures to the free market to operate as successfully as it can.

I can’t remember the 1960s all that much, and I wasn’t in Parliament until right at the end of the 1970s, so I saw most of that from the outside and would have no special insights on it. But as an external observer, it seemed to me that this philosophical gulf between the two parties was harmful to the economy and, of necessity, harmful equally to regional development. I don’t recall at that time a vast amount of focus on regional development in the sense that we understand it today. The onus in the 1960s and in a good deal of the 1970s was about dealing with the severe economic problems that existed in those two decades, and I’m afraid the relatively smaller issue of which part of the country was doing well, and whether we were following the right policies for it, was of secondary importance to dealing with the problems of inflation and debt and unemployment which, for clear and evident reasons, dominated the thinking of governments in those two decades.

Q: When you get to the 1980s, the view was that if you can get the economy stable and growing and attract foreign direct investment, that would bring benefits which would be shared?

There was a strong belief beginning in the 1980s in what I used to call ‘trickle-down’ policy: if the economy was doing well, the wealth generated by the economy as a whole would gradually trickle down to embrace everybody, and everybody would benefit. In retrospect, that didn’t happen. It trickled down as far as investors. It trickled down as far as the leaders were concerned in industry and commerce. It trickled down to the innovators. And it trickled down to those who had very special skills. But it did not trickle down sufficiently to those at the bottom of the heap.

As a result, there were many people who did not benefit from the growing wealth of the country. And of course, the very fact that trickle-down didn’t happen to the extent we hoped is one of the many reasons that led to such a disenchantment with government and, in my view, to the Brexit vote. You saw a similar occurrence in the United States – where the result was not Brexit but Donald Trump. So the argument that we’re all in it together was not true when it came to sharing the growing wealth of the nation.

Q: Would you say during your Premiership that you recognised and attempted to tackle the fact that wealth wasn’t trickling down and being shared?

We were frustrated about that. We were keen to see it trickle-down. But it did not succeed as we hoped. The amount that we were able to do was insufficient to make that happen to the extent that is necessary. Yes it was an objective, not the objective. But I don’t think that we were able to fully counter the alternative forces. One of the these, perhaps the biggest one, was the way we all misread globalisation. Because globalisation had a great deal to do with the concern so many people felt that their lives were not improving while those of others were. We misread that. The intention was there; the outcome of policy did not meet the intention.

Q: How much did you view the agenda you pursued from 1990 onwards as a break with the agenda that had been established in the 1980s?

Consider what the circumstances were at the moment I became Prime Minister. We had inflation very close to 10 per cent. We had interest rates which had been 15 per cent – I actually inherited 14 per cent. So we had sky high interest rates; rapidly rising inflation which rose, to just under 10 per cent; unemployment was beginning to rise and growth was falling. We were undoubtedly heading for a recession, in part because of the general situation in the world, in part because of the 1988 budget. It was a grisly economic scenario and the primary concern, evidently in those circumstances, rather like the 1960s, was to deal with the problem that had bedeviled us for 40 years, and that was inflation. Getting inflation down was very painful, but it was the primary objective. We didn’t see we were going to get sustainable growth up, or sustainable employment up, or increased well-being of the nation up, until and unless we brought inflation down and made business more competitive. So that was the dominant objective.

Most of the things I would have liked to have done as Prime Minister were not possible because of the overriding need to deal with the economy. The economy began to improve in the second half of 1992: that wasn’t apparent to the public at large, it’s sometime after the economy improves before it trickles down to the average taxpayer. They still remember the gruesome policies that are still overhanging and the many economic side effects of those policies.

Let me elaborate a little on inflation. Inflation to some people is just a word, just a number. But from my background I knew exactly what inflation meant. Inflation meant that the week lasted longer than the money, and that is a frightening proposition. I saw that as a child, I understood it very plainly, which was why I was obsessed with inflation. When we entered the Exchange Rate Mechanism (‘ERM’) we did not do so as a prelude to joining the single currency. We did so because we had tried every other conceivable way over 20 years to bring inflation down; and every time successive governments had backed away from the pain it caused. So I saw the ERM as an external control to bring down inflation that we could not tamper with – as successive governments had tampered time and again with anti-inflation policies. That wiped a great deal of the policy page clear. Until inflation was tamed that there wasn’t much – there was a certain amount obviously – but there wasn’t a great deal that we could do for the main objectives that we had in terms of increasing growth and increasing productivity.

Q: What were your chief successes and frustrations in terms of regional and local economic policy?

In terms of identifying successes, I think a detailed examination of those parts of the country that succeeded – the university towns and others – might throw up some serious answers to that particular question. My gut instinct is that policies such as enterprise zones, city challenges, the various forms of public private partnerships and development corporations, all had some success, but I have a caveat with nearly all of them.

What I am much less sure of is whether their success genuinely added value to the economy; or whether it was a redirection of investment that we would have had somewhere at some stage. I don’t know the answer to that. My suspicion is that a large part of it was redirection. That’s still helpful to regional policy because, if you’re dealing with parts of the country that were in a very sad state, a redirection of investment is helpful in itself. But it isn’t actually an incremental add on to the economy unless it is in addition to what would otherwise have happened across the country as a whole.

The overriding frustration and failure right through the whole period that we’re talking about – not just the 1990s – was low productivity and greater inequality. That is what, looking back, makes me despair and you can take your pick of culprits for that. I touched on one earlier – I think political dogma is a culprit. I think inadequate education and the wrong education is a culprit. I think, in a lesser way, so is class distinction and class dogma. So, obviously, is every Government over six decades.

There’s also an instinctive opposition to change through self-interest or instinct. I’ll give you a practical example that’s relevant to business as well as individuals. The planning laws need changing, they’re much too restrictive. But if we are to house the nation, or provide sufficient jobs for the nation, we need to have quicker, cleaner, more clear-cut, less expensive planning laws; and yet NIMBYism, the not in my backyard syndrome, tends to stand in the way of it.

So all those were culprits acting against the ideal policy mix. As far as an overall assessment is concerned, my instinct is that the only way you can measure whether you’re successful or not is by creating a better standard of living. That, after all, is the purpose. And in the period between the war and 2015, the standard of living for the vast majority of people did improve quite dramatically. But the failure was it left too many people behind and created too many inequalities as it did so.

Q: What was your goal – what were you trying to achieve?

In essence, it was to make the UK the enterprise centre of Europe with an open and dynamic economy. I know they’re clichés, but that’s what we were about. We had hoped that we would gain world trade and gain world investment by keeping the cost of business down and profits up. And the degree of inward investment suggests there was a considerable success there. We thought that that was a recipe for prosperity for all. We promoted incentives and rewarded success. But we were tripped up yet again by the fact that it was not universal. It was partial.

We wished to reduce inequality. Certainly, like every government, we touched it at the fringes – but we didn’t eliminate it or get remotely close to doing so. We set policy to try and reduce unemployment and, from 1992 to 1997, that succeeded extremely well; but we were less successful in boosting equality. I know we’ve touched on these things before but, as I said earlier, growing wealth stuck in the pockets of a minority and didn’t trickle down to everyone.

I’d like to add something about globalisation. We all saw globalisation, overwhelmingly, and I think that’s true of all parties, as a pretty good thing. It increased world trade, it increased prosperity and, in some countries, most obviously China of course, it took literally hundreds of millions of people out of abject poverty. That’s the good side of globalisation. It was also helpful, we thought in the 1990s, in creating a convergence on values: on equality, on human rights. I would argue that each of those three things are being lost over the last few years. But in the 1990s we thought globalisation was helping them.

But then there was the downside to globalisation. When you look back on it, what did it actually do, apart from the growth of world trade and the other successes I touched on? Certainly, as far as the West is concerned, it transferred low paid jobs from the West to the Far East, particularly China, and it cut off that trickle-down of wealth we talked about and any feeling of improved well-being for people on relatively low incomes. And that created resentments: Trump, Brexit and all that. The voting patterns of Brexit seem to me to be a direct legacy of globalisation and inequality. I don’t think governments saw that. I don’t remember anyone arguing that case, at any time in the 1990s or the noughties, governments didn’t see it and I think that was a failure of government collectively, over quite a long period. We were one-eyed on the subject of globalisation.

Q: Did different departments show differing attitudes towards regional growth and to engage in devolution?

I didn’t see a great deal of difficulty with engagement. Partly because our eyes were looking at the central issue of the economy. But once departments were told what we wished them to do it, they did it. We had some ministers who were very keen on regional development, Michael Heseltine being one example, Ian Lang being another. I don’t recall any great institutional difficulties.

There was sometimes difficulties over money with the Treasury – but that’s the Treasury’s job, particularly the Chief Secretary’s job. He’s there to be the abominable ‘no-man’ sometimes and say ‘no we can’t afford it’. But, by and large, I think there was a broad measure of agreement that we had to move in that direction; I can’t remember any occasions when we really had to step in and deal with serious problems between departments dragging their feet against what was collective policy.

Where I think we did get something wrong was that we did undervalue the capability of local government and overvalue the capability of central government. There was a reason for that. That reason springs from the disputes in the 1980s, between local authorities and the Treasury and the Conservative government, over spending levels: many local authorities clearly wanted to spend more, did spend more, to an extent that from it began to rattle the overall borrowing requirement. And there was a good degree of dispute and agonising over that. That hostility dragged on for quite a while. I hope it’s something we’ve now left behind. But it was an atmosphere in which government centralised too much, and underestimated the abilities of local authorities.

Q: Was the more trend towards decentralisation and devolution just not available to you because the arguments of the 1980s were so proximate?

It was partly that but that’s not a full explanation of it. The atmosphere was not good. But then you began to get policies where local authorities were invited to bid for money. That was easier because, once they bid for money, it was for a specific purpose. It was effectively ring fenced and you knew what you were going to get for your money. It wasn’t money just going into the local authority system and then being used in ways, perhaps, that the government didn’t think were productive to the economy. There was a slow movement towards devolution through the idea of elected mayors.

Devolution was a problem. It was firstly a constitutional problem and I had very mixed views about that. I had no doubt that Scotland and Wales could adequately govern themselves. That was never a concern in my mind. What was a concern was my fear that devolution would be a stepping stone to independence. That was very much in my mind and I am a conservative and unionist so I didn’t wish to see that. I was happy, in principle, to devolve more money. I was happy to approve policies that were important for Scotland or Wales. But I wasn’t prepared to go down the route to full devolution.

When the Labour government produced the Devolution Act late in the 1990s, soon after they came into power, I didn’t oppose it. What I did oppose was the fact that devolution was granted to Scotland and Wales with no complementary changes in England to ensure there was more equity than in practice occurred with that Act. I fear that devolution has, as was always likely to be inevitable, eased the path towards independence. Whether we’re going to get there, we don’t yet know.

At some stage, under this government or the next, there’s going to be another referendum in Scotland. Who knows, by then, where opinion will stand. But devolution did create a problem because of the constitutional fear of losing Scotland and the concern that if you lost Scotland, what incentive would that be for those who would wish to move Ireland or Wales into independence as well? That was a huge blockage to the devolution of policy. Not the devolution of money, but the devolution of local control, extra control, over the money. It was nothing to do with the skills of the regional authorities. It was everything to do with the constitutional question of whether we would move from a devolved settlement to an independence.

Q: You could either argue that to move towards Scottish and Welsh parliaments and devolution for them was a mistake. Or you could argue that, if that was being done in Scotland and Wales, it ought to have been done more effectively in England too?

I think there would have been a real danger in that. The genie of devolution is out in Scotland and Wales. But if you had devolution in England, I’m not sure the genie wouldn’t be even more damaging. We’re seeing a very strong nationalist trend in England. Please don’t think that wasn’t there in the early 1990s. The day I walked into Downing Street, I felt as though I had my feet straddled across a gaping great hole called Europe and there’s a good deal of nationalism in that argument. Nationalism is a very powerful emotion and one that supersedes economic logic and national well-being. I have always been very wary about any policy in England that might have encouraged nationalism. My route would have been much more the devolution of resources within the existing structure – and not the establishment of an English Parliament.

Q: There was a Scottish and Welsh Development Agency prior to political devolution and Labour introduced Regional Development Agencies in England to play the same kind of role that the Scottish and Welsh Development Agencies played – was that a better way of proceeding?

It was more what I would have preferred in the 1990s. Looking at it from the perspective of today, I’m not sure it would have been enough. I made the point a moment ago about independence being an emotion rather than an economic calculation: if we thought England wasn’t free, there’d be a huge uprising. I don’t like the thought of an independent Scotland or an independent Wales, but I can understand why people who are Scottish or Welsh feel very strongly about it. I’m very conflicted on this.

Q: The Regional Development Agencies were then abolished in 2010 and replaced by Local Economic Partnerships which were much weaker. Then came the directly elected mayors. How do you assess these developments?

I welcomed the local mayors because they were a familiar idea. Michael Heseltine was keen on local mayors in the early 1990s. We discussed it then and, for a variety of reasons, it didn’t become policy. Frankly, we were so beset on every side by economic problems that they, perhaps, didn’t get the priority they should have done, or we might have done it earlier. But it seems to me, from what I have seen in the last few years, that the regional mayoralties have been a great success. And I rather wish, in retrospect, we had been in a position to introduce them in the early 1990s.

Q: When we talked to Michael Heseltine, his big regret was that the redrawing of the local map to have bigger local authorities was ducked in the early 1970s. Was that something he raised with you when he was Deputy Prime Minister to redraw the local government map?

I can’t recall but it’s highly likely that he did. Every time Michael came into Downing Street he had ten new ideas. So I’d be surprised if he hadn’t raised it. He was very innovative and had learned a great deal from his time in Liverpool – and was very struck by the difference that could be made. I think mayors have been, so far, a much greater success than one might have expected. A much greater success than I expected. And they’ve also attracted some quality people to take the mayoralties, which was a question at the time.

In the early 1990s, I was dubious that any member of parliament, with the possibility of getting to the Cabinet would exchange that role for the mayoralty locally. But now, of course, that has happened. You can see a sort of Joseph Chamberlain reborn. Joe Chamberlain was a very substantial local government figure in the 1880s and 1890s and you can see the mayoralty is modelled on that sort of idea and how much they may achieve. The problem with the mayoralties, it seems to me, is exactly what their boundaries are going to be and what you do about the rural areas. But I am now fully committed to the idea that a key part of reducing inequality and lifting the regions is the election of quality men and women as mayors.

There is one problem with it that is worth airing. In terms of local authorities having the power to help lift people out of economic difficulties, one option would be to grant them much greater tax raising powers so that they can pay for their own policies, and they don’t have the Treasury on their neck. But it doesn’t work.

The problem is that the local authorities that need to spend the most money are mostly those that have the least economic development and the lowest wages, so it would be the poorest people who would need to raise the largest sum of money. You’re never going to avoid the need for subventions from central government and I can see quite a lot of difficulty. If you virtually removed subventions from central government for some of the wealthier parts of the country and piled a great deal more money elsewhere. That would be a difficult political act to pull off. So there is a real problem about increasing devolved tax raising powers to pay for local expenditure. You are always going to need subventions.

Q: Did you have specific theories or international examples what an effective, well-functioning local or regional economy looked like to help guide policy?

As pragmatic politicians we looked at ideas we thought would be successful and tried them, rather than having an embracing philosophical view of how it should be done. Which is why there were so many different options, like city challenge, a whole range of public private partnerships. If something works we should do it – and not be put off by party philosophy from times long ago.

We did think different ideas might be needed in different parts of the country. But we weren’t sure which would be more successful – which is why over that period we tried a whole range of options: a repeat of the enterprise zones that Geoffrey Howe tried in the 1980s, regional development grants, the development corporations, all sorts of innovations. And we were observing to see which ones worked best in genuinely creating additional performance in the regions.

So specific theories weren’t the way we thought and I’m not sure, looking back at what other governments have done, that it was how they thought either. Perhaps we should have thought more widely. I think the debate now has moved on quite a bit and broadly in the right direction. But many of the earlier fashions and fads that we had did not seem to me to have been wildly successful.

When there’s a problem, governments must be seen to do something. The trouble is, having done something, it is some years before you can assess whether the something you’ve done was really worthwhile. And sometimes it isn’t, which is why you see so many changes in policy. I think the investments that worked best included development corporations, public private partnerships, City Challenge, where people were actually bidding for the money. Those are the things that we were beginning to realise worked best.

In City Challenge, they had to bid for funds and therefore utilise the funds in a way consistent with their bid. Public private partnerships had a mixture of public sector and private sector ethos, which was plainly better than either having one or the other. It’s for those reasons that we began to think they were a success.

What we didn’t look at, and might have done, is what we could have learned from London and other parts of the country that had been successful above the average. We might have looked at that more closely. London, of course, is different from anywhere else and the success of London was certainly helpful to the central exchequer, it yielded a great deal. It was an advertisement for UK efficiency and the lure for inward investment. So we did tend to think of London as something different. I won’t call it a milchcow, because it wasn’t, but it was certainly a huge success.

Q: Huntingdon in your constituency and other nearby towns like Stevenage and Peterborough clearly benefited from London’s success and proximity?

They benefited from access to it. When the M11 was built it made a big difference to Huntingdon – and Huntingdon now has grown enormously bringing in jobs with it. It’s not just housing. There’s a great deal of new industrial estates and jobs offering high quality and, in some cases, pretty highly paid jobs as well. But it was all within easy reach of London.

Q: Does London’s success end up being a detriment or difficulty for the parts of England that are further away from London?

We might have used the success of London to divert more of their financial skills to places like Edinburgh and elsewhere where there was a financial base. But we didn’t and it wasn’t really an issue at the time. We saw, in London, something of enormous success in the UK that was doing extraordinary well and nobody really wished to lay their hands on it. I’m afraid that was the truth of the matter. It’s still an open question. London is really a state on its own, and it’s intriguing to see how it is developed.

Q: Do you worry that the distribution of spending across the whole of the UK on transport and science ended up being too London biased?

Of course it was too London biased. It was, and is, too London biased. But that is partly because that is where developers and others wish to go. It is where they can make the best profits. It’s where there is a clear demand. It’s an area that justifies the expenditure. It’s chicken and egg.

But, that said, it is now necessary to devolve that expenditure. If you look at the West Country, access for companies wishing to set up or even to send their produce to or from there, is very difficult. Infrastructure is plainly crucial as part of the Levelling Up process.

Q: Do you worry that we’ve been too city focused and haven’t worried enough about the towns – or is focusing on cities the right way to make sure the towns benefit too?

It doesn’t seem to me that they’re necessarily alternatives. It’s beneficial for the cities and nobody would wish that not to happen. I think the argument that if the cities benefit then we all benefit is a trickle-down argument of a different sort and I’m not at all sure that I buy that argument. I do think we’ve got to look at the towns, and we’ve got to look at the rural areas.

The question is how we do that. They may not be big enough for regional mayors. If you make the regional mayoralties too small, then they have too little resources, too little clout and too little end product. I think we need to find a way to bring the towns and the rural areas somehow into a larger structure that will have the clout and the resources to help them. I don’t claim to be an expert on this. One option might be to up end the whole of local government to create unitary councils with boundaries coincident with local economies – whether the local economy was a city, or a collection of towns, or the two of them combined. However, others may have better ideas.

Q: Sounds great?

It could be very messy. I wouldn’t wish to be the minister trying to do it.

Q: But politics aside it would be the right thing to do?

Yes it would, absolutely the right thing to do. Another option is bringing in the rural areas around the cities or the small towns into the ambit of the city Mayors. In terms of infrastructure that has a lot to be said for it.

A third option least favoured I think because it would be least productive, would be combining rural areas with their own elected mayor. The problem is that rate precept would be pretty miserly, I suspect, and there would just be huge subventions from central government. I don’t really regard the third of those three options as a very credible one. But the first two, very difficult to implement, you’d have rebellions in all sorts of towns and cities and rural areas because you’d be tearing them up by the roots, their historical allegiances; but it might, over the next 50 years, be the most productive way.

Q: The other alternative is only to have devolution and extra resource in those places who opt to have an elected mayors and leave the other areas outside – that’s is what has happened over recent years?

It doesn’t end inequality. It probably exaggerates it. That would be the drawback as far as I can see. In terms of being able to implement the policy, it would be easier to do that. In terms of actually getting rid of the problem of inequality, in all likelihood it’s going to worsen it. It might also move the population out of those very poor areas and completely denude them. So I think there’s a lot of difficulties. It’s not a policy I would wish to defend.

Q: Should there be an East of England mayor, a wider Cambridge mayor, should you put Cambridge and Peterborough together?

That might end up like putting Glasgow and Edinburgh together, or Rangers and Celtic. But if you look at it from a purely economic point of view, the answer is yes. Politics is sometimes impossible because politics aims to do two different things: it aims to do what is right and it aims to do what is popular. The two things don’t always go together.

Q: What are the important lessons for Governments to take on board as they pursue Levelling-Up or balanced regional growth?

One bee I’ve got in my bonnet is vocational education. I would like to go back to what I recall existed in the 1950s when, in the state sector, you could choose at about the age of fifteen whether you wished to continue either an academic or a vocational route. If we’re going to take the sort of policies that we are following at the moment on migration and not bringing in people with skills, then we are going to have to develop those skills ourselves. In which case, I think we should start developing them at 15 or 16 in school, for two or three years, before the youngsters leave.

The point I’d make about Levelling Up is that it isn’t a short-term policy. This is a policy for 25 years, perhaps longer and it’s got to involve a lot more than infrastructure: training, education, health, all of those things are going to have to be included. And there is a party political point about Levelling Up. Since it is such a long term policy, in any normal historical cycle it is going to have to continue through changes of government. And if it is right, as I believe it to be, and if it is have to going to have to continue through changes of government, which I’m sure it will do. It would be in the national interest now for the three main political parties to come together and agree long term objectives to minimise those changes in policy – you can’t put down a complete detailed programme. If Levelling Up is a policy in the national interest, then it calls for a political agreement to make sure it’s implemented over a very long period of time.

Historically, to borrow a phrase from the past, solemn and binding agreements don’t have a great deal of success. But we do need something like that if we’re going to make sure that this isn’t another policy in which one side can say, ‘Ya boo sucks we’re going to level up, you’re not’. Never underestimate the capacity of Party politics to damage a good idea.

There’s little difference that I can see in the fundamental objectives of the Conservative Party, the Labour Party and the Liberal Party. They may have different methods, but, often, they have similar objectives: to reduce inequality and improve overall wealth. And statesmanship – if I could draw a distinction between statesmanship and politics – would be for the three parties to come together and agree broad heads of agreement so that we can be certain that the policy of levelling up – and the investment to improve productivity and create a fairer society – can continue until completion.

With very large investments, maybe investment in a new nuclear programme in the light of getting rid of fossil fuels, there would need to be an agreement on very long term areas of expenditure that spread through several parliaments. I don’t think agreement is impossible. I think such an agreement would be hugely reassuring to external investors and hugely reassuring to people who could actually see that they weren’t just being offered Levelling Up as a political ploy, but it was something that was actually going to happen to benefit the next generation. I’d be very much in favour of some sort of concord between the parties to ensure that it continues over a very long time. I may be whistling to the moon, but I think it is a whistle worth having.

ENDS