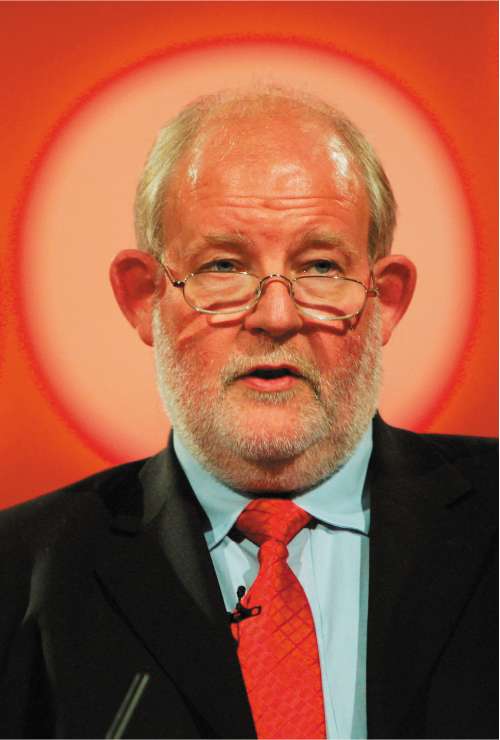

Charles Clarke was the Member of Parliament for Norwich South from 1997 to 2010 and served as Secretary of State for Educations and Skills from 2002 to 2004 and was Home Secretary until 2006. He now holds Visiting Professorships at the University of East Anglia, Lancaster University, and Kings College London, and works with educational organisations internationally.

This interview was conducted on 30 November 2021.

Q: Could you tell us a little bit about your role in growth and regional policy over the past few decades?

I suppose I’d say my governmental experience on this aspect was principally as secretary of state for education and skills, which I saw as a key aspect of our growth strategy. Though I continue to believe those skills were never given enough priority. But we can talk about that. In addition, when I was chair of the Labour Party in 2001 to 2002, the Chancellor, Gordon Brown asked me to be on one of his committees looking at some of these aspects. Other than that, I’d say my experience isn’t really traditionally academic, but more in the governmental sense. I wrote a book recently on the challenge facing universities in which I argue that the role of the universities in addressing growth, devolution, regional inequalities is very important and is given insufficient attention. But I think that’s quite interesting.

Q: Could you give us your initial assessment of policy over the past few decades? What do you think have been the key successes for what we now call Levelling Up? What have been your key frustrations working on it?

I think my biggest frustration, and it’s absolutely central, is that we haven’t developed an adequate theory of how to promote economic growth at a time of globalisation. So if you take the North East of England as an example, if the North East of England loses coal, steel, shipbuilding, what is the economic activity which replaces that? And if it loses those things because of an increasingly competitive world marketplace in which we are insufficiently competitive, what does anybody do about that? Is it inevitable state of decline or not?

Now, obviously, the answer to that – I say obviously, maybe it’s not obvious – obviously the answer to the question is to find a future-looking prospectus for economic activity, I don’t even mean economic growth, economic activity in that geographical region. There have been a whole set of different measures suggested to do with that kind of thing in the past. Past Labour governments, for example, encouraged investment in such areas in South Wales valleys, for example, and in particular, Japanese investment came in a variety of ways. Nissan is a major Japanese car manufacturer which has gone into the North East. But I don’t think that has been sufficiently thought-through, it’s all fine but is it long term? And the natural advantages which led to coal, steel, shipbuilding being in the North East are to be replaced with what?

I think that is a central, problematic issue which has led to decline. If you look at the decline in the mining communities around where Ed [Balls] used to represent in Yorkshire, you could see desolated communities, is the only word I can use, with not much sense of hope or alternative. Now, various very, very short-term things will develop, like cab companies and that kind of thing. Some people talk about tourism, about which I’m pretty sceptical in this area, but the question of ‘What is the economic advantage of, say, the North East of England, or say Yorkshire?’ is a core question which needs to be properly addressed in each particular case and wherever it arises.

Now, there are a number of answers to that question. Infrastructure is an interesting one. Transport infrastructure, road, rail, telecommunications infrastructure for an organisation’s ability to operate and so on. And I’d say our record on that kind of thing is pretty partial. There’s some okay examples of it, but really only okay. I wouldn’t say we’ve had a great approach to really being able to solve the infrastructure problem.

You’ve got a people issue which I’ll call loosely skills. What are the skills and capacities of the people in such a community to do what they need to do in the future? I had an approach, when I was Secretary of State for Education and Skills, I don’t think that Ed disagreed with this – in fact, I think he sought to do it when he was at education and skills as well – about sector skills councils, essentially saying for each of the, say, 30 economic sectors of the economy: bring together the businesses themselves, private or public sector, all those associated with the businesses, the trade unions as well, and so on, the education institutions, both within without the sector, and say in a particular sector – say IT – develop a framework for people to be able to pass through the skills that they needed at a variety of different levels in a variety of different institutions. Where this had traditionally been done in the UK was a couple of sectors, engineering and construction in particular, where there was a long tradition of this.

But it was important, in my view, to try and generalise it to all sectors of the economy, and we had a couple of successes, places like IT, as I say, but in general, it was quite difficult to move it further forward. Though I have come across a number of examples where something useful has been done.

I think an absence of consistency about doing that, notably in the last 10 years, has led to a view that these are all quangos and not much value. And it has not really happened, because the core issue about skills is the commitment of employers, both public and private sector, to skill development in their economic sector. I don’t mean just of their workforce, though that’s also true, but of the economic sector. But of course, to do that, going back to my North East example, you have to have a sense of what skills are the appropriate skills, which will really help.

But we in Britain, I think we’ve had a pretty sterile debate around words like ‘apprenticeship’.The whole fundamental question about how you bring together the worlds of education on the one hand and work on the other, at all levels, is critically important. We had some degree qualifications, foundation degrees. I specialist skills programme was designed to bring employers into relationship with the local education system so on. But it’s a very, very patchy and inadequate system, so I’d only give that, at best, four or five out of 10 and really much lower than that in the recent period.

Going back to the transport and telecommunications infrastructure I’d possibly give that a bit more, six out of 10, but not much more. So that’s the infrastructure foundation and then you’ve got skills foundation. But then you’ve got the conception of how you bring together the key interests in a given area, Ed referred to the LEPs [Local Enterprise Partnerships] and the RDAs [Regional Development Agencies] and so on, to really develop an economic strategic focus that brings together the public and private sectors in thinking how you develop particular areas. And for me, the most striking thing is what I’ve read about the role of universities within that, where there’s significant evidence in the States in my view, that there are places where, for example, the decline of the Rust Belt has been, if not reversed, at least slowed into steadying reverse by the engagement of universities in their local societies and their local economies. I believe the general story is of universities not engaging in their local economy and society very much and a sense of isolation of the universities or even entitlement. But I think that gives you the best possibilities of seeing how you can think of a new economic attractor to regions like the North East. Now, if you look at the universities in the North East, there are universities which are trying to do that to some extent, places like Sunderland University are trying to do it. But there’s a real discussion about the extent to which the university sector as a whole is facing up to what it could or couldn’t do in these areas.

Q: How much is this about getting the right level for policy? Should what you have just talked about be happening at the city level or the local government level or the subregion? Should the strategic focus be outside of the centre?

I don’t think localism is a very helpful word actually. But I mean, there’s going to be issues in each particular case about whether it is the city, the local subregion or whatever. But you’re fundamentally right. Unless something is actually possessed by the locality, and I agree one can have a discussion about what I really mean by possession in the locality, then it’s not going to happen. And the idea that in Whitehall or Westminster I can say, ‘Okay, well the way to develop Sunderland is like this.’ I think that absolutely doesn’t succeed at all. You have to get a genuine commitment from organisations in localities.

I think, actually, our failure to reform local government has been a major problem in this at a variety of different levels. I favour, for example, unitary local government, which I think helps you do this in the areas which aren’t unitary, which aren’t that significant in Britain but nevertheless are real. It really holds it back. And I think the idea that businessmen and women locally are going to be the people who really drive it – I think it’s probably not true, but I think you need elected local leaderships to be directly involved in it. But the catalyst for this change depends on a couple of people at a locality who really can draw people in and focus on a particular example. I don’t, for example, know enough about who the first forces were in Yorkshire to make that happen or whether it should be Leeds, Leeds and Bradford, or in Sheffield or whatever. I think it’s quite a difficult question because there’s been lots of issues and difficulties doing it, but the fundamental point that it has to come from that level, I think, is true.

Q: What’s your assessment of the capacity at the local subregional level, both in the public sector and in the business sector, to be able to do this? When you talk about lack of local government reform, is that about power or is that also about capability?

The capacity is very, very variable. I think, for example, that pair in Manchester, Richard Leese and Howard Bernstein, was a very effective operation and was able to do stuff. But I don’t think that was happening, for the sake of argument, in Newcastle – hardly at all. And I think you can occasionally get entrepreneurs who make a big difference. But I think if you look at the left, certainly our experience in Norfolk, was you didn’t have people who were movers and shakers, I wouldn’t say, really involved in that. There were people who were doing their civic duty like showing up to the meetings, but I wouldn’t say it was a lot more than that.

Q: If they had more power would it have changed the dynamic?

It might well have done, but that was a particular weakness of Norfolk. Just to explain: Norfolk is a part of the country which are so-called ‘two-tier local government’. So you had contest between county and city, which wasn’t true in the areas of South Yorkshire or in most of the North East, which I was just talking about, where you have a unitary system of local government.

Q: Did you generally see a political divide in Norfolk and Suffolk between the city and the rurality?

Very much so, even quite harshly. So there was that issue and I do think there was a serious issue of capacity. I’m involved now with Lancaster University that’s trying to do stuff with Morecambe Bay and a regeneration of Morecambe Bay, which is on the west of England, north of Liverpool, and I was up there last week. And the extent to which the university has the capacity to really make a difference there is quite limited or even to be able to talk to local people in a sensible way because there’s a sense of entitlement and so on that goes on that makes serious dialogue very problematic. But if you had an approach which was trying to generate that kind of activity, I think there are a lot of people who could put resource in and do it well. But the trick is you’ve got to really think about what your economic generators are in a given locality, and I think that’s quite a difficult exercise. And it’s not at all clear for each particular locality what the best generators of that actually are.

Q: It’s interesting, if you take that example, your Lancaster University, you’re quite a big economic player with a biggish footprint. Should you, in general in this kind of conversation, be talking to Morecambe or to Lancashire or to a super Manchester output area or to the North West?

One of the problems about the way this government’s approached it is there’s no kind of consistency to the patchwork and so there are whole chunks of the country which are completely left out of any, quote, ‘devolution’, unquote. In principle you need to talk to all of those things, of course, but they have to have a sense of coherent direction and sincerity. I thought dividing the country into regions, which we did about 1998, even though there were controversial decisions as to who was in or out of whatever region, was the right thing to do.

I think we lost the regional devolution to the North East because Prescott refused to accept, and I made this argument very strongly in cabinet committees, that you could only get a positive vote for a local regional government if you had gone unitary beforehand. Otherwise, you are voting for locality. That argument would carry the day as indeed it did. But I did think the region was the right way to go. I thought the big government spending departments could do a lot. I looked, for example, in education when I was there, at taking all the schools capital programme that were there and just saying, ‘We will decide nationally how much goes to each region’ and you literally sign one decision, you wouldn’t look at individual projects, and you devolve all the schools capital programme to civil servants in the regions of the country. So you say the eastern region gets however many billion out of that and they would then decide where the money was spent in that region rather than it being decided centrally. And the argument for doing that, in my opinion, was that itwould give more possession over the decisions locally. I thought you’d get better quality decisions and once you had a significant resource like education, capital spending or, for that matter, health capital spending going into particular regions and decisions being taken by local politicians in that way then I thought you’d get a better chance of a sense of some momentum behind a more devolved structure.

Q: So finding that economic plan say for Norwich or the wider Norwich economy, it felt better doing that in the era of the Eastern Development Agency than post-2010?

100%. I always have to be aware that Norwich is atypical for the reason we’ve talked about. It is a two-tiered area, and those are relatively small geographically in the country as a whole. But you’ve got to get to a state of affairs where certainly big capital decisions, transport infrastructure and so on are taken at a much more local level. Now, I don’t think those can be taken at the city-level, so I do think you’re talking about a regional type of basis. And I don’t think it’s absolutely critical that the regional authority has to be elected. I think you can imagine the regional authority, which is done by nomination bythe elected local authorities. So going to elected RDAs isn’t absolutely central to this, but it is central that a given region which has a substantial budget by comparison to most countries, can decide on a lot. And if you take the capital programme, you can do a lot. Now the question, can you do much on the current budget? You can do something on that, I don’t think you do nothing, but it’s not as clear and easy as it would be on the capital budget, and my approach would have been to steadily try and roll that out. That doesn’t deal with the questions I was talking about earlier on i.e. what’s your regional identity? But remember, if you take DWP [Department for Work and Pensions], I remember very substantial arguments with the benefits agency, talking to the local people where decisions were being taken about where the benefits went, which were being taken nationally, which were completely insensitive to what real employment needs were for the people there and skill development of people who are unemployed there.

Q: Did Whitehall speak with one voice? Was there a similarity or difference in views between the different departments?

Well, there was no commonality. I mean, it was worse than that. There was no discussion. I mean, you couldn’t even say there was a difference of view because each of the departments was going on and doing its own thing, and the way you brought it together was a very difficult process. We did have a process later on, when David Miliband was at DCLG, of trying to get a coordinated approach across different areas. But I would not say that was a very easy thing to do at all. In fact, I’d say you simply couldn’t say it existed. But the problem about that, if you took getting people back to work, I do believe that the local benefits office in Norwich, given a budget of X, would do a better job than simply carrying through the rules determined by central government. The same in Liverpool and Merseyside. And the problem is the legal change implied for breaking a system that says every individual has a certain entitlement by law was obviously very, very problematic and could give rise to injustices. But fundamentally, what you wanted in these enormous spending agencies where there was any flexibility at all, was that locally decisions should be taken about how to use that resource to enable the local economic needs to be met.

Q: The Technical and then the Learning and Skills Council and the sector skills councils were a way of trying to move decision making more locally. But local government or the RDAs, would say that actually [the Department for] Education kind of wanted to keep things separate. Where did that culture come from?

No question, that’s true. Well, it’s just the silo culture that exists. Essentially, what happens is education in London operates under a set of laws about the running of the schools. The professions are trained in light of that situation. The funding follows that down and that applies everywhere.

I mean, if you take the reform which I’m most self-critical of, it was bringing together education and children’s social services. And though I thought that was a logical and right thing to do, and I think there are many arguments for it, the fact was education and children’s social services had completely different cultures, completely different professional formations, completely different funding streams and so on and bringing them together to work in a coherent way, which I thought was desirable, was in fact very difficult and led to all kinds of problems of various descriptions, and that applies to each of these professional cultures that you’re talking about.

There was a tension – I don’t know if you remember when I was Secretary of State –with the Treasury about: did you put money through the learning skills councils locally or through the sector skills councils nationally. And there was a real tension about that. And I certainly thought that you ought to be looking at the sector skills councils nationally for the actual training and all the rest of it. The accreditation process is because we have a national labour market, but I can certainly see the argument for operating it locally in relation to certain skill development aspects in a particular locality. But we know, I mean, I don’t know if you think this is right, but I don’t think we ever got to a consensus about where the leadership for that was in any given locality and the absence of that, that demotivated people and lead different issues to arise. Part of that was politics, I think it’s one of the arguments in a policy level which I had with Gordon about some of these things, but part of it was much more profound. It was exactly what you say about the Education department not wanting to lose its control. They saw that’s what it was about and transport the same, health the same. There was a massive issue for all of these [departments] about to what extent you could allow any local autonomy at all.

But I would say as a government and as a party we didn’t have a coherence about that issue. We didn’t have coherence, though there were some common themes that were quite good. We’ve now moved to a situation where there is no common themes and no ideas at all.

Q:Are there any developments in the last 10 years where you think they have been good? Do you think we should have been much more regional in 1998?

Yes, absolutely. And so you’ve got to do that with police as well. It was my point about trying to get from 43 police authorities down to about 12 or 13. But you need to have a coherence to it all. And the borders need to be at least coterminous, which requires some difficult situations and how you put the jigsaw pieces into those borders you can have a discussion about, but they’ve got to be at least coterminous.

Q: Which is not what’s happened. It’s been evolutionary, hasn’t it? And therefore messy. There’s some people say that’s the only way to do it.

Well, that depends. They’re prepared to face up to political challenges of various issues as they come along. Certainly when you look at the majority we had from ’97 onwards, I think that with that kind of majority it’s possible to move it on and we could have done. But for various reasons, people weren’t ready to do that. And I don’t object to directly elected mayors. I’ve always been quite sceptical about them, and I certainly don’t think they have a kind of answer that Tony [Blair] and [Michael] Heseltine thought. I don’t think that they clarified the debate about these things in any very effective way. Police and Crime Commissioners, I think a massive backwards step, I think completely wrong. But I do think having some coherent patchwork is quite important actually, and I don’t think that we’ve got that.

Q: And how about accountability? If you have more devolution to, say, the eastern region, can the accountability happen through the national parliament, media or through some kind of accountability counterpart?

What I actually argued for was regional select committees, rather like the grand committee that you had with Scotland and Wales before devolution. And I thought and think that if you take the eastern region, to take that example, having a committee of the House of Commons which is all the MPs in the eastern region. And they then, with proper resources and so on, having hearings on health in region, education in the region, whatever, would generate a lot, get media going towards an interest going towards it. It was always opposed on the grounds that, for example, in the eastern region you’d always have a Tory majority. But I never saw that as an argument against it, as with Labour always having a majority in the Scottish in the grand committee.

Q: Implicitly there you’re saying that the source of the accountability comes from Westminster, even if there is a regional dimension to the scrutiny, that you aren’t arguing for there to be either an elected or unelected or kind of hybrid regional assemblies?

Well, the first thing I need to say I’m against an English Parliament. I’ve always been against an English Parliament. I know John Denham goes for it, but I don’t think it’s right. I’m not against elected regional assemblies. I think it’s possible that you have to define it properly and carry it through, and it may be that regional select committees are away on the road to that. But the problem is, if you completely exclude MPs from this kind of stuff, you’re in a very dangerous place. What are MPs doing? If they’re not looking at the health spending in the eastern region, what are they doing? If it’s all left to the elected regions, in my opinion, that could only really go with significant reduction in the size of parliament, which I think there’s a good case for. But it’s such an enormous change. I don’t know how you’d actually get that agreed.

Q: So do you have reflections on what can we learn from the rise of London in policy terms for the rest of the country? And do you have views on whether London is a help or a hindrance to this?

Well, I think the idea that you can improve the situation the rest of the country by decreasing the economic growth of London is basically mad. I mean, at the end of the day, London is a very dynamic, very driving economy still today. And any idea that you can somehow detract from that I think is unwise. Ed knows a lot more than I do about the financial services sector in London, and whether it’s significant or otherwise, and he might disagree but I think the idea of shifting, building up the financial services industry in Leeds or Edinburgh or whatever, won’t really succeed.

I do think there’s an issue about regional government in London. When the Greater London Authority was established, there was a question about what you were doing with the office for London of the national government. But they had enormous powers, for example, on all the health spending and so on. And I think that there’s one too many tiers in London probably. We should probably try and reduce it by one level. I don’t know what Sadiq Khan is doing about making that argument, but I think there is a case, as we were talking about before. But of course the London boroughs are quite significant. I think they’re probably quite an appropriate size, actually, the London boroughs, to deal with the level of decisions they have to take. But I think the fundamental thing is London is a very dynamic modern city. The one thing I’m proudest of myself in my history at Education was the London Challenge programme, which turned the performance of London schools from being the worst performing schools in Britain to the best performing schools in Britain over a period of 10 to 15 years. And that was about a whole set of measures for which central government impetus was necessary, but was essentially locally-led.

Q: Building on that final comment, why was the London Challenge not rolled out or sustained as much across the rest of England?

Well, that’s an absolutely excellent question. Essentially, the London Challenge was successful in London. There was an effort to do it in the West Midlands Black Country, but didn’t really succeed. And also in one or two other areas it didn’t really succeed, and the question is, why not? And that’s a very good question. It still goes on. And I think that the overall approach that we had in London Challenge wasn’t put into place as effectively as it needs to be over those periods. That’s my recollection.

Q: If you take that London success and then you think about Norwich or Norfolk, Greater Manchester, there are some people who say that inevitably, London’s success while good was a drag on the other cities from graduates moving to London. There are other people who say, actually, the most important thing you have to learn is you have to have a very big city focused strategy so that you allow Manchester and Leeds to do what London’s done.

I basically take the latter view. You’ve got to encourage growth in other areas, and if you try and do it as an alternative to London it won’t succeed. But I think it takes you straight back to where we started this conversation, which is what is the economic attraction of somewhere else? Manchester, for the sake of argument, what is it that drives itself? And if you try and allocate resource or skills or something from London to Manchester, I don’t think it will succeed. And Manchester has to have its own drive. Leeds has to have its own drive. Now it’s an interesting discussion that you touched on there about the relationship with the city in the towns nearby. Again, in your case, where you represented, the relationship between Sheffield and the surrounding community is an excellent question, very important question which is going on now through a slightly false town slash cities discussion.

Q: Where do you come out there? Are you more in the city pole of growth? Or do you think you have to sort of broaden the footprint?

I’m more the city area of growth actually. I don’t think putting your eggs in the basket of Stevenage is going to really turn it around. What are you doing with that? I think it’s a very interesting subject. I’m interested to meet you down in it. What are you actually doing? You’re going to try and produce a policy proposal?

Q: When you think more widely internationally, are there particular models or experiences you’ve seen from other places outside England or outside the UK which could influence your thinking?

Not really. I always quite admired the Scandinavian-type models, and I was going to say, some American cities, but that’s not really true actually. I’m not sure that’s really true. I think one of the problems about this is people in a genuine scientific sense think there’s big comparability across different countries, but I’m actually very sceptical about that. I think the cultural issues here, obviously the economic issues are as classic as they were through the 19th century: where is the coal physically located, where are the rivers and so on , where are the generators of economic activity. But I think you can make two common comparisons across quite different cultures, quite different societies. I remember people trying to compare Marseilles and Liverpool – both great ports. Apart from that one speaks French and the other doesn’t speak English. You haven’t got a state of affairs where – I just think people make these comparisons too loosely across different countries.

I think the reason why universities come up as important in this, if they’re well led and done in a constructive way, is they’re tremendous agencies for improving local capacity across a wide range of different things.

There’s a book called The Smartest Places on Earth: Why rust belts are the emerging hotspots of global innovation. by somebody called Antoine van Agtmael and Fred Bakker. And just to quote paragraph in the book: it shows how rust belt cities such as Akron, Ohio, in Albany, New York, and it talks about the state of New York Poly-Nanotech complex in the US and Eindhoven in Holland and becoming the sense of global innovation and creating new sources of economic strength though coming from rust belt areas that had been written off. They identify a series of cities: Dresden, Lund and Malmo in Sweden, Oulu in Finland, and so on where they think this is happening. And when I read this book, I really commend for your reference, and if you just look at the page 104 of the book and 105. It really did demonstrate and what these authors emphasise is the entrepreneurial importance of the connector. This is usually an individual who has sufficient vision, energy, networking capacity and drive to assemble the working partnerships and engagement that brings together university industry, government and others to make change happen.

The authors of this book emphasised that the connector can come from any one of a range of places, that they must have the ability to make the connections that are essential. They also emphasise the pragmatism, ambition and collaboration of local and regional politicians, entrepreneurs and scientists and so on. But the point about the connector is the connector could never be somebody from central government in Westminster or Whitehall. It’s got to be somebody who does it – the problem about the elected mayor is that they may or may not have the capacity to be a connector. The other book is called Our Towns, and it’s a quite an entertaining book by James and Deborah Fallows. It’s been a bit of a vogue book in California. A quirky account of five years of journeys across the US to look at a wide range of communities hit by globalisation.

The conclusions about what made towns succeed in finding a prosperous post globalisation future. One, people working together on practical local possibilities. Two, picking out the local patriots. They talk a lot about who are the people who really stand up for the locality and are looking out for it. Three, making the phrase of public-private partnerships something real. Lots of people go for what I call ‘notepaper partnership’ where you put on the MP and so on. But they’re actually just notepaper. The question is, what are the private partnerships that really work, whether you’re talking cultural industries or whatever. A well understood civic story, very important, narrative about the place. Having downtowns. They emphasis having a downtown rather than all just going out to the suburbs, which is probably more important in the American context and the US. Six, being near a research university. Seven, having and caring about a community college. Eight, having distinctive, innovative schools. Nine, making themselves outward looking and open. Ten, having big plans. If you get the book, you’ll see an interesting range of places they visited, that these were the things they identified as what they thought made some of these places succeed and others not.

Q: What is the one thing where you think ‘Actually, if I had the chance again, I’d do it differently’?

The really good thing we did is the London Challenge, no question about it, because the quality of education in London is such a big issue and was such a big issue. By the way, it wasn’t just about academies. I mean boroughs like Hackney, where you went down the academy route and that’s fine, it’s perfectly all right. It’s not just about academies, it’s about a whole range of things. I think getting the fundamental structure of local and regional government is really quite important. And then you’ve got to get and readiness of central government, which can only come from political leadership, from ministers and the prime minister to really drive central decisions which don’t have to be taken centrally but could be taken locally. The example, I give is the school capital programme. There’s no reason why the decision about schools in South Yorkshire should be taken in London at all. You can take a big decision that said South Yorkshire is getting x billion and so on. But try and get decisions forced down locally and you can argue the toss, whether that’s through direct election to an authority to by indirect election, by some kind of regional select committee approach. Very different ways that you can try and tackle it. But you do need to get those decisions local, and that we never achieved.

ENDS