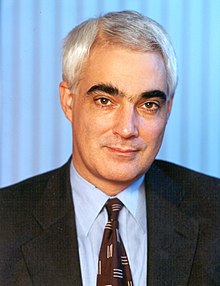

Lord Alistair Darling was Chancellor of the Exchequer from 2007-2010. He served in the Cabinet throughout the Labour Governments of 1997-2010, across the Treasury, Work and Pensions, Transport, Trade and Industry and the Scotland Office. He is a life peer in the House of Lords.

This interview was conducted on 8 March 2022.

Q: Could you tell us about your role in growth and regional policy over the past few decades?

I was in government for thirteen years. I was in the Treasury at the very beginning as Chief Secretary, and at the end as Chancellor during the financial crisis of 2008-09. I was Secretary of State for Transport for four years, with a short period at the Department of Trade and Industry (‘DTI’) as well. I was a Member of Parliament from 1987 and 2015. Representing a seat in Edinburgh, I have a slightly different perspective to what the UK looks like as if I was representing a seat in the middle of Westminster.

Q: What is your overall assessment of growth and regional policy over the past few decades? What do you think has been the main success and the main frustration?

From the period of the 1960s onwards, we did not have a regional policy in the UK. We had interventions. We had macro policy that had benefits throughout the UK. But we did not look at what was happening up and down the whole of the UK: where traditional industries were coming to an end; where population, particularly the skills of the entrepreneurial populations, migrated to the cities. Whilst undoubtedly London’s success has benefited the whole of the UK because of its sheer size, diversity and enterprise, we did not make sure that everyone living in the whole of the UK – and indeed in London itself – actually benefitted from these.

There are many examples where governments of different political colours did good things to try and arrest that. But I don’t think, to be blunt about it, that in the last 50 years either of the main parties ever sat down and thought, ‘what are we going to do to spread power, by which I mean economic power, throughout the whole of the UK?’. Where we have done it – in for example the devolved administrations in Wales and Scotland – there are serious questions to be asked as to, even with those powers, what did it do? It’s not at all evident that that much has changed.

Q: How would you characterise policy in that earlier era?

After the Second World War the country needed to be rebuilt. One example of where there was a concerted effort to devolve power was the building of the New Towns in all parts of the UK. What they did there was critical. They built a town that was not quite the complete article, but: it had a high street; it had cinemas; it had places of entertainment; it was a place people wanted to be. In time, they grew very proud of those towns.

Too often today, an intervention has been to build a road, building a railway line, or a particular intervention with a company. As often as not, it’s resulted in even more people leaving a particular area to go into the cities. Now, don’t get me wrong, these things can be important. But I think the key if you want to regenerate and decentralise power in Britain is, you’ve got to ensure that in those areas you’re seeking to rebuild, that you have housing that people want to live in, good quality schools, health – a community in every sense of the word, where people want to be. One of the things you do need is a place that people can work in. One of things we could learn, incidentally, from the working-from-home era is that you don’t have to go into an office in the centre of London to do your work. You can do it in the north of England, in the Western Isles of Scotland. We should capitalise on those things we now know work.

Q: How do you think of the post-1997 governments compared to what came before?

During the Thatcherite era, the general ethos was: government is bad. It got in the way of doing things. People were losing their jobs when the pits or steel plant closed, but don’t worry, they would find a job somewhere else. Of course, that didn’t happen. An awful lot of people were just left unemployed, then, often as not, moved onto disability benefits. In some areas of the country – London is the preeminent example – it worked because there were an awful lot of jobs. If you lost one, you could get another job and so on. Not much attention was paid to the basic infrastructure of the country, quality of housing and so on.

In the period after 1997, the Labour government took a very different view. It felt that we had to get the right macroeconomic climate, which we devoted a lot of time to giving people confidence we could do. But the welfare of people – general wellbeing – was at the centre of what we were trying to do (which is why we introduced tax credits and so on).

Whilst we built, I think, a better and a happier country than it was, what I don’t think we did was enough to make sure that we decentralised power, economic power, and opportunity to different parts of the country. You’ve got to remember that if you look around England, for example, ‘outside London’ is not all the same place. There are striking examples of successful cities like Manchester, Leeds, Newcastle, Bristol, for example. But there are lots of places in other parts of England which lost out because whatever the industries were, they moved away, and people were left behind. Similarly, Scotland is not just one uniform entity. Edinburgh is very different from Glasgow. But Glasgow and Manchester are two examples of where cities, after the industrial base that they had built themselves on had faded away, reinvented themselves on the back of good quality universities, on the back of attracting good quality firms to come and work there. This emphasises my point: if you really want to build and to rebuild the country, you do need to decentralise. You’ve got to have the right governmental structure to do that, but, critically, unless you make places that people want to be, it won’t work.

Q: How important is decentralisation for realising that goal? Much of what you are talking about – transport links, bigger universities, housing and health investment – could be delivered without any extra powers for local or regional government?

I think you are right that at a UK level you can do an awful lot of things. For example, making sure there’s enough money to build decent railway lines. When I was the Transport Secretary, we upgraded the whole of the West Coast Main Line which cut journey times. It had contributed to what was happening. You’ve got to make sure there’s enough money to make sure the university sector is good and it’s thriving.

Often as not what really matters is how you deliver the service on the ground. Everybody knows that in the whole of the country there are some very good entrepreneurial councils, and there are some terrible councils that don’t really do anything. If you take an example where things have worked well, Manchester has got a sense of identity. It’s got a sense of prosperity and a good place to be that is not shared in some other council areas not too far from it. Newcastle has the same thing: a sense of civic pride and achievement that shines out in the North East. It depends on, from my experience, a charismatic leader of a council and an equally charismatic, resourceful and entrepreneurial chief executive. You can make a hell of a difference.

Frequently, when I was doing transport, Greater Manchester was always at the door saying, ‘these are the things that we think would make a difference in our area, where Whitehall does not know best, if indeed Whitehall knows where the actual place or street is’. They can make a difference. If you don’t have that, you won’t succeed. Equally in the health service, there’s been there’s some very good examples of where the NHS is world-beating, world class. There are other examples where it’s failed pretty badly, usually because of poor management as much as anything else – because the money allocation isn’t that much different.

Or if you take Scotland, for example – where obviously the macro climate is set by the UK government – the Scottish government’s record since it was set up in 1999 – has not been that great. If you look today, if you live outside the Central Belt of Scotland, you will get a very different view as to what’s been going on. They’ll say powers have been taken away from local government. I’ll give you one example: the Scottish government recently published an Economic Prospectus and is going on about what we could do in the Islands. It didn’t mention the fact the ferry services are breaking down and you can’t get on and off because they’ve been unable to build enough ferries to replace an ageing fleet. It’s an example of where, looked at from London or Edinburgh, the world can look very different to where if you look at it from Stornoway, or you look at it from Yarmouth or Cumbria.

That’s why I think devolution is not just that it’s the right thing to do, but it also gives people ownership. They took the decision, or their representatives took the decision, and they did things that they think may make a difference. Of course, they will make mistakes, like all governments, national and local make mistakes. But I think that devolution is a state of mind as well as a state of economics. If you don’t get both right, then it’s not going to work.

Q: Across the many offices you held in Whitehall, would you say there were differences in departmental culture with respect to devolution?

In the five government departments where I held a senior ministerial position, I didn’t detect in their culture, ‘we want to gather power unto ourselves’. It just doesn’t happen that way. The same accusation is made by the local council, ‘they’re only doing it because they’re in it for themselves and they want the power’.

There are some things, like economic policy, where it’s very difficult to see how you can’t have a policy in relation to spending or taxation that isn’t central. You can have variations, but someone’s got to take an overall view of what’s good for the country. There are other obvious things like defence.

I think there has sometimes been a reluctance – particularly if you are decentralising spending power outside the spending departments – where the department doesn’t feel that it’s got absolute control over it. You can get around that problem: you can fix the ceiling so you can’t go and spend whatever it takes, because it’s got to be paid for at some stage. But where you spend it, whether you spend it on a rail project or a road project or on building a new school or doing something like that, there’s no reason why we can’t do that. I would not buy the argument you can go down to the parish council level and decentralise everything. But I think where England does have, for example, recognised regional centres we could.

Looking back, we wasted far too much time on talking about having elected regional assemblies and stuff, to counter the Scottish one, which nobody really wanted. We didn’t spend enough time saying, ‘well, what can we do in their place?’ You don’t have to invent them. Some areas are there already. All I would say there is just beware. Once you go outside that circle, no matter where it is, you’ll then reach another problem with the towns that weren’t in that centre. They also have their own reasons to feel excluded.

The States is different because it’s so vast, but every other country in Europe, even ones that are smaller than ours, are decentralised. It’s a good thing. Of course they’ve got their federal governments, but they decentralise what they don’t need to run from the centre.

Q: When you were in Trade and Industry, did you see a tendency for officials to think in national-sectoral terms, or were they more spatially conscious with decisions like business support or inward investment?

There is a bit of that, and there can be a clash, but I don’t think it’s a case of having one or the other. Scotland had something called the Scottish Development Agency – up until the Conservatives abolished it – which was charged with helping areas develop, helping firms come in and develop. It had alongside that a sectoral strategy. At that time the big thing was getting people from outside to come and assemble things in Scotland, as the case may be.

I have never seen the difficulty in having an argument that – to take the example of the transition to a net zero economy – you’re not going to deliver on the basis of people doing bits and pieces here and there. Apart from anything else, it will need serious money being spent on it. Some of that serious money is going to have come from the UK. Equally in energy policy, it’s very difficult to see how you can do anything in energy without having a national policy.

That doesn’t mean that, in how you apply those things – whether it’s the environmental, whether it’s developing high technology – that we all have to be the same. Some areas have got very good, specialised universities. Other parts of the country may have other strengths. Devolution isn’t all about simply taking the whole and slicing into 10 different parts and saying, ‘there you are, that’s what you’ve got’. If you want an area to thrive, you’ve got to have people who understand it, people who can take ownership of it, people who are answerable to it, people that are elected, and give them sufficient levers to do it. You don’t want to end up with the situation we have in Scotland too often which is, ‘we can’t do it because it’s all the fault of being part of the United Kingdom’. You’ve got to give people sufficient power and then say, ‘okay, you go ahead and do it’. But that doesn’t stop you having a national strategy.

Q: In Transport, did officials like the idea of allowing local priorities to decide how the money was spent?

Transport is slightly different. The problem with a railway line is that trains are running over it from the north of the country to the south. If you have trains that are crossing it and going only a few miles or so on, you’re using the same track. There’s a slight conflict of interest in there. Although our railway network is national and a train leaving London and turning up in Glasgow stops in many different places, the regional needs are slightly different. I think you could only operate that in some degree of partnership.

It can be done, is being done in many areas. It’s a pity that, having decided to build High Speed 2, the opportunity cost, as they say, means that there’s going to be very little money left over to do the stuff that we really need: particularly connecting the north of England and lines that run East-West rather than North-South. As for getting to Glasgow and Edinburgh, well, it ain’t gonna happen in my lifetime or my grandchildren and their children. There’s a great example of building a project that’s not regional, it’s not national, it’s just a vast waste of money.

Q: Is there a trade-off between national standards and uniformity, and local discretion? Others we have spoken to cite inflexibility around Job Centres, for instance, when delivering active labour market programmes?

When I was in the Department of Social Security, then the Department of Work and Pensions – which is 20 years ago now – there was very little call to devolve the benefits system. When you think about it, there are massive problems. If you’re paying a certain rate of benefit and someone says, ‘well, in London, it’s X plus two, in Newcastle it’s X minus two’, how can that be right? It’s the same mouths you’ve got to feed, the costs are broadly the same. The policies we had to encourage people to go into work, they were national as well. I think where you possibly could devolve things if you give a regional area a pot of money that it can spend for work incentives, I wouldn’t have any problem with that. It would be quite interesting to see what works and what doesn’t. I think to try and decentralise your basic system of welfare payments, you might get one or two people gaining from it, but you’d get a hell of a lot of people complaining because they’d lost out.

One of the key things we did was to change the whole culture of the Department of Work and Pensions, from being an agency that simply paid out benefits and treated people fairly cursorily. You used to go into the benefits agency offices with glass windows where you couldn’t speak to anybody. You had to yell through a crack in them. I remember visiting one in Birmingham one summer, very hot day. There were people openly dealing drugs in the place, there were fights going on, there were young mothers with children desperately trying to get help. Then you have got the staff who were cowering behind it because they didn’t want to go near this gathering storm in front of them. About a week later I was at a different office where we were trying out something different, where when you arrived you were met by someone at the door who asked what you wanted, you were sat down in a room, and you were talked to like a human being. That has become Job Centre Plus. It was an experiment in a client-side office and it changed the whole culture. It’s one of the reasons that I think when the financial crisis came eight, nine years after that, unemployment didn’t rise as much as we thought it would. We were very good at getting people turned around and getting them into other jobs. You could not do that on a local basis. Similarly, if you look at something like the New Deal, it could only work as a national project.

What I’m arguing for is not a complete fragmentation of what government or governments presently do, but recognising there are in certain areas benefits in having a different system. Try it out, see if it works. It may work in one area, may not work in another area. English education, for example, is very fragmented compared with the Scottish provision in terms of who actually does it. But if different things work in different countries, why not let people have a go at it? What’s critical is you’ve got the national funding to make it work, as well as basic qualifications and so on. I think we need to be more flexible, and that is as much a state of mind as it is opening different pots of cash in different parts of the country.

Q: What do you do for the places that are just outside of the cities and major urban centres?

I don’t think there is a one size fits all. These are individual towns. There’s a reason why they’ve got the problems they have. There might be different solutions. I was talking a few moments ago about the transition we need to make in generation of electricity, heat and so on. Other countries have been remarkably successful in getting the construction of the turbines and the other kits you need in their country, which creates jobs, very often in places where there were no jobs before, or at least jobs have been and gone. That’s where I think there is ample scope for national government to intervene. That in itself doesn’t amount to regional policy. I think you have to look at each of these areas.

Sometimes they change in themselves. One of the things that has changed dramatically, for example, is the hospitality industry. Ten years ago it didn’t exist in the form that it did today. Obviously, COVID-19 has played havoc with it to some extent, but there’s a lot of good jobs. People had more money to spend going to visit places, staying in hotels and so on. If you look at England’s seaside towns, for example, which really went into the doldrums when it was so easy just to climb on a jet and go off to Spain and so on, there’s lots of things you can be doing there. But you wouldn’t apply the same policy to say, Scarborough, as you would to somewhere in the West Midlands. It’s a different thing. That doesn’t stop you decentralising as much as you can. It doesn’t say there’s no room for national government. But it means you just need to be a wee bit more flexible. Don’t assume that if the macroeconomic climate is okay, it’ll trickle down, because the chances are it won’t.

Q: What are your reflections on working with the Regional Development Agencies (‘RDAs’) in terms of their capacity and effectiveness?

I think it’s like so many other things: there were some good RDAs and some not so good. It depended principally on who was chairing it, the chief executive, as well as the rest of the board. I think it was a big mistake of the government subsequently to get rid of them; freeports are not an answer to it. I would never encourage anyone to reopen elected regional assemblies and things like that. They’re a complete distraction to my mind. Nobody wants it.

Local government is important. You can easily arrange for more local government representation to make sure that things work together. But I think the thing that RDAs did, and can do, is bring a focus, bring additional resources, can create the sort of environment where firms want to go and invest. Don’t knock that. Firms want to get a feel for the place, to feel ‘people want us, and we can do things’. We’ve got resources: not just cash, but universities and so on. I think the RDAs were a very successful innovation. A lot of it, like everything else, comes down to the people who are operating it.

Q: What was your evaluation of local and regional political leadership?

Take two examples: Greater Manchester knew exactly what it wanted. They met beforehand and they didn’t deviate from the line when they came to see us, whether it was transport or in DTI support. They were very good people there. They were united – even if behind the scenes the two areas weren’t at all happy with it, they’d done a deal between themselves. If you took the North East, there are about six local authorities, and as far as I could see, none of them could agree with each other on anything.

I’m not a great identity politician, but identity does matter – if people feel they are doing something for the area. Greater Manchester owned the airport. They used that as a magnet to get firms to come in from all over the world around it. There was a feeling, if you go to Manchester, of ownership (even though it is clearly situated in one particular part of Greater Manchester). I think what you need to create is a sense of purpose. Part of that is making sure that you’ve got the right structures. Don’t ask me how I would legislate to get the right calibre of person, people leading it, or the chief executive, because that’s probably the pot calling the kettle black.

Q: Should central government be voluntaristic or directive in encouraging local cooperation?

For some policy – for example, we are going to build regional rail links in England, rather than a national HS2 type thing – only a central government can decide that. In the vision I have for decentralisation, particularly in England, you’re doing this throughout the whole of the country. What you’re saying to people is, the policy of the government is to improve these rail links: you can either be part of it or if you don’t want to be part of it, that’s fine. You go and do something else. But don’t assume that we’re necessarily going to fund something else in its place. It still may be necessary because of the nature of the railways. If I’ve got a ‘go ahead’ regional authority in East Anglia, and one in Manchester, and I would like a line to go from one to the other, at some point I’ve got to drive through an area that might not be cooperative. There’s no perfect system I can come up with.

Don’t get me wrong, having been a member of a national government for 13 years, I can see the benefit of doing things nationally – whether it’s the tax system, the benefit system, the incentives in the system, public spending generally – without which, frankly, you’re not going to get anything. If levelling up would happen without getting money it would have happened already. It needs public expenditure. All that must be at the national level. How it’s delivered and where it goes… there’s nothing wrong with having a good and maybe different local angle to that.

Q: Are there areas where you wish you had gone further in terms of decentralising across any of the portfolios that you worked on?

Transport is an area where I think we could have gone further. It works well in London because it’s happened in London since the railway network was built, and so you didn’t have to struggle too much. There’s a very strong London view: the commuter network is pretty central to everything that you do. Elsewhere it’s fine, but it’s not centre stage. I think our government did many good things. But I think we should have sat down at an earlier stage, and thought, ‘how do we decentralise power? How can we make people feel they own it?’

Where we went wrong in England was, we were persuaded that what was good for Scotland and Wales was good for England – and we’ll start in the North East of England. It became very apparent that, unless you were actually involved in politics, you were not remotely interested in creating yet another body to go on top. If you look at the North East of England, there was an awful lot done by both parties. If you look at the Nissan plant, if you look at the engineering that grew on the back of that, there’s a great success story there. I think the government, certainly in the years after 2010, could have done a lot more to support it. But Scotland illustrates the point: just because you’ve got a government in Edinburgh, as opposed to one where most decisions were made in London, doesn’t mean the policy gets any better.

If you take the North East, I think you’d have been better trying – which I did try – to persuade the six big authorities in the North East to work together. If they came to me and said, ‘we want a road as opposed to railway’, then it would have been a lot easier. But there was no unanimity there. That wasn’t just my view. It was a view shared by some of my colleagues who were the Members of Parliament there.

In relation to Scotland, I think the real difficulty was an ambivalence towards investment in industry. In Edinburgh we have relied for far too long on the financial services industry and I remind you that RBS and HBOS dominated the landscape, both physically and metaphorically. It’s taken a hell of a knock. Glasgow is a bit more entrepreneurial in terms of trying to get people to come and invest. But in Scotland, we need an economic policy concentrating on four or five things. The paper published recently has 26 different objectives.

Q: Has devolution to Scotland led to a bigger focus on Scotland’s distinctive economic policy?

I don’t know. It’s not because it decided that, but it has been absorbed in other things. Scotland has not been helped for the last 17 years: it has been absorbed by a debate about Scotland’s constitutional place and everything else takes second place to that. We ought to have been able to capitalise on the North Sea oil boom. We have in Aberdeen. There’s people now in Aberdeen who do not work in the North Sea, nor have they ever done it. The expertise they have is clustered around Aberdeen and they export the skills around the world. Aberdeen and its surrounding are pretty prosperous. Glasgow has benefited a lot from inward investment, from American firms coming in. Edinburgh, to my mind, has rather rested on its laurels.

For a lot of Scotland, we have not had a policy where we can capitalise on the things we’re actually quite good at. I touched earlier on one of the things I would like to see us explore: having the Home Office, for example, employ people in the North West of Scotland to do work that used to be done in London, because you can do it remotely. Working from home has given us an example where you could get people not to leave the areas they grew up in and to go and live in the city – maybe in not very good quality accommodation – but instead to work from home and go into the office once a week or once a month. I don’t see any sign of that opportunity being grasped at the moment. We’ve talked a lot about the English reasons. We still have to tackle the point that London is critically important to the UK, but bits of London do not see the benefit of all of that.

Q: Have directly elected mayors in England been a step forward?

I’m really not in a position to comment on mayors. Like everybody else, some are more vocal than others. I don’t think a mayor is the answer to all this. It’s good that you have someone to articulate an area’s grievances, but I’d rather see what we could do to sort out those grievances in the first place. Which is why I think you needed to go a wee bit further.

You ask me about the years after 2010. I think what exacerbated it was the policies the Coalition adopted. For many people living in the areas we’re talking about, their incomes fell even more sharply than anybody else’s. It exacerbated an already difficult position. If you don’t have the resources, you’re rather stuck. You will end up creating a lot of empty vessels, and they will just stoke people’s cynicism and exasperation.

You need a competent, entrepreneurial, growth-driven national government. But you also need the structures that can build on national policies, adapt and amend them as appropriate, and also give them the financial clout to do that. There will always be a case they’ve never got enough. But they can do things. If it works in just about every other country in the world, why can’t it work for us?

Q: If resources weren’t a constraint, say for Scotland, what would a genuinely different economic approach look like?

Let me give you a national example. Scotland’s attainment gap between children coming from more affluent areas and less affluent is growing. It is getting terrible international reviews. We used to be very proud of our education system. It needs fixing because if you don’t have a well-educated population, you are always going to struggle. It’s not fair on the kids themselves.

In relation to industrial development, with the transition to a low carbon economy, we have a massive opportunity. We’ve got engineering know-how in Aberdeen – we’ve got it in other parts of the country – where we could be looking at building some of the stuff that we’ll need. Yet, where the Scottish government has intervened, it’s been singularly unsuccessful so far. I mentioned financial services. Yes, it’s had a knock, but the services industry in Scotland is still, as it is in the UK, very important. What you above all must do is to create the sort of environment where people want to come and work here. Not ones who look over the border and say, ‘I’m not so sure about that’. That’s why the political climate, particularly the Scottish one, is very important if you’re asking yourself what’s going to happen here over the next 20 years.

Q: Is enough done to make more parts of Scotland attractive for people who want to live in and work from? Are things too Edinburgh-focused or too Glasgow-focused?

Although the Scottish government is in Edinburgh, it is not particularly Edinburgh-focused. If you look at Edinburgh, it can stand with the very best of the country on a whole number of factors. I think if you look at quality of housing or health outcomes, it is still the case that somebody living in one part of Glasgow is more likely to live eight years less than someone living seven or eight miles away. That’s something that we should not be putting up with. It hasn’t changed much in the last 20 years. It’s very difficult to define a place where people want to be, because for each person that’s rather different. You can’t just build a road or a bridge. If that worked, the Humber Bridge that Harold Wilson built would have worked wonders. Whereas in fact, all the evidence is that there’s a bit more to do there.

Q: What are the most important lessons for us to take away as we look to the future?

I think it’s important to have a strong and stable economic environment and a competent political outlook. Take trade, for example, which we have not touched on. We’ve got to have a sensible trading relationship with the European Union. We’re not going to go back, but we need to have a sensible arrangement with our next-door neighbour. Everybody else would do it. We should be doing it.

Having done that, you then need to ask yourselves, ‘how can we devolve power and opportunity to different parts of the country, particularly the English regions?’ I think that’s something that’s been overlooked for far too long. Just remember this: if you’re going to do it, it isn’t just about pots of money or building the odd rail or extending a road. It’s about quality of life. It’s about making places that people want to go and live in, where they feel confident, they can live there, their children can grow up there, there’s opportunities there, and they don’t have to go somewhere else to get on, as it were. None of this is beyond us. Most other countries do it, and I don’t see why we shouldn’t either.

ENDS