STAHR’s history is literally written on the walls of the Loomis-Michael Observatory! The organization dates back to the 1990s and has been responsible for the student-led custodianship and operation of the Observatory ever since. The Observatory itself is significantly older, entering service on March 5, 1976: Neil deGrasse Tyson was a frequent visitor during his days living in Currier House! Between our vintage records, the constellation paintings produced during the ’90s, and The Crimson clippings spanning decades of STAHR operations, we have a rich and vibrant history — one we’re eager to share with you!

Read some STAHR Alumni Testimonials, or add your own!

Jump to Early History • Installation • Before STAHR • A STAHR Is Born • Modern Day

Digitized STAHR Logbooks

Our logbooks record all the visitors who have passed through the observatory since its installation in 1976! Each one tells a story, and we’re currently in the process of digitizing ALL of them. Due to WordPress limits on file sizes, most logbooks are broken up into a few PDFs.

- February 4 1976 – June 6 1977: 2/4/76 – 11/1/76, 11/2/76 – 6/6/77 (the first Neil deGrasse Tyson logbook!)

- June 6 1977 – June 29 1978: 6/6/77 – 2/28/78, 2/28/78 – 6/29/78 (NDT visit on 11/12/77!)

- July 6 1978 – November 28 1979: 7/6/78 – 11/28/79

- More logbooks coming soon

- September 23 2007 – May 25 2009: 9/23/07 – 10/31/08, 11/1/08 – 5/25/09

- June 7 2009 – October 28 2010: 6/7/09 – 4/1/10, 4/1/10 – 10/28/10

- October 20 2010 – August 7 2011: 10/20/10 – 3/21/11, 3/22/11 – 8/7/11

- August 7 2011 – July 8 2012: 8/7/11 – 11/8/11, 11/8/11 – 3/30/12, 3/30/12 – 7/8/12

- July 5 2012 – September 24 2013: 7/5/12 – 11/17/12, 11/17/12 – 3/16/13, 3/17/13 – 9/24/13

- October 3 2013 – May 13 2015: 10/3/13 – 10/27/14, 10/27/14 – 5/13/15

- May 14 2015 – April 3 2017: 5/14/15 – 5/11/16, 5/11/16 – 4/3/17

- April 13 2017 – May 4 2019: 4/13/17 – 2/3/18, 2/6/18 – 5/4/19

- May 4 2019 – February 23 2022: 5/4/19 – 10/8/21, 10/8/21 – 2/23/22

- February 23 2022 – April 12 2023: 2/23/22 – 5/16/22, 5/17/22 – 10/24/22, 10/28/22 – 4/12/23

In the Beginning, 1955–1966

“I hereby transfer ownership of my telescope, camera, and dome to Harvard University” –Charles Michael, 1966

In late 1966, Harvard received a very interesting letter from one Charles R. Michael. An alumnus of the Harvard College Class of 1961, Charles had spent his four years at the College as a Biology concentrator in Winthrop House. He went on to earn a PhD in Biology and Organismic and Evolutionary Biology from the (Griffin) Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in 1965.

As 1967 approached, Charles packed up his belongings, moved out of his home in Bucyrus, Ohio, and was confronted by one very important question…

What shall I do with my telescope?!

You see, Charles was not an average Harvard student. His father, Walter J. Michael, was the president and owner of the Ohio Locomotive Crane Company and a very wealthy resident of Bucyrus, Ohio. In fact, one of Walter’s side ventures was breeding standardbred racehorses, and during his time as a breeder he raised approximately 1,600 horses. Walter served as President of the United States Trotting Association — the regulating body for harness racing — from 1958 to 1969. When he wasn’t breeding horses or selling cranes, Walter was doting on his son, and in 1955 he had given young Charles a 10″ refracting telescope for Christmas.

By the mid-sixties, Dr. Charles Michael had moved out and was no longer able to use the telescope, and so it came to pass that on December 28, 1966, Charles gifted his telescope to the Harvard Astronomy Department. Whether the gift was motivated by the Christmas spirit or the tax deductible is impossible to say.

Read Charles’ letter donating the telescope to Harvard!

Jump to Logbooks • Before STAHR • A STAHR Is Born • Modern Day

The Telescope’s Journey to Harvard, 1966–1976

“Every student who comes through the doors of the Science Center should be encouraged to look through a decent telescope” —Dave Latham, 1974

When Charles donated his telescope to Harvard in 1966, the Science Center was merely a fantasy in the heads of Harvard administrators and planners. The site was actually occupied by the unused Lawrence Hall (home of the “Free University” of students and Cantabrigians) at the time. Big plans were afoot, however. Harvard used a $12.5 million gift from Polaroid founder and Harvard alumnus Edwin Land and support from other sources to build the modern Science Center between 1970 and 1972. During and before construction, Harvard had no place to store a telescope (much less the 22′-diameter dome Charles had included in his gift).

Naturally, Walter began to grow rather impatient as years went on. By November 1971 he had had enough and wrote a testy letter offering $10,000 ($75,000 in today’s terms) for the legal return of the telescope that was still on his estate. Harvard deflected, promising that the telescope would be the centerpiece of the under-construction Science Center. Construction wrapped in 1973 and the primary concern promptly switched from a lack of space to a lack of funding. An estimate in January 1974 suggested a cost of $75,000 ($470,000 today) to move the telescope to Harvard. It had just spent millions on a new Science Center, but the University was unwilling to foot such a large bill.

At this point, two key heroes enter our story. The first is Alfred Lee (he preferred to go by his middle name) Loomis Jr., a former Dunster House resident in the class of 1935. Lee’s father (the elder Alfred Lee Loomis) had been instrumental in the Allied development of radar during the Second World War, and Lee himself was an accomplished yachtsman, 1948 Olympic gold medalist, and venture capitalist. Lee gave Harvard enough money to cover part of the telescope’s cost, but it was still not enough.

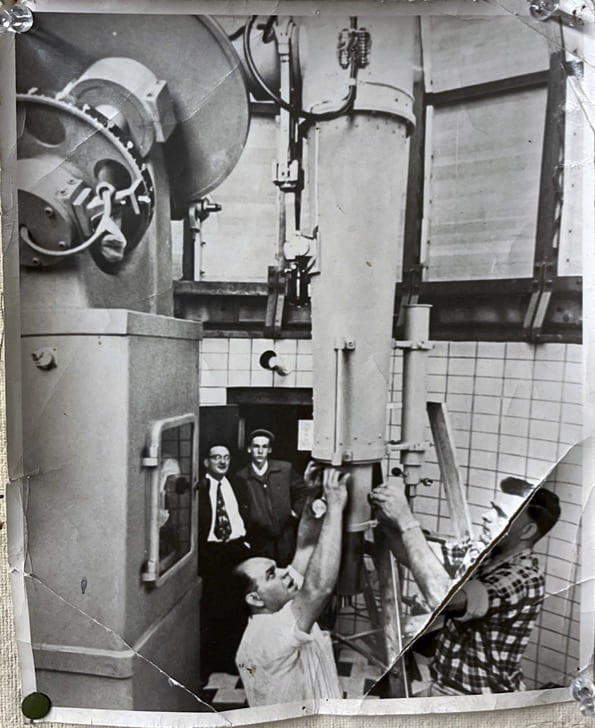

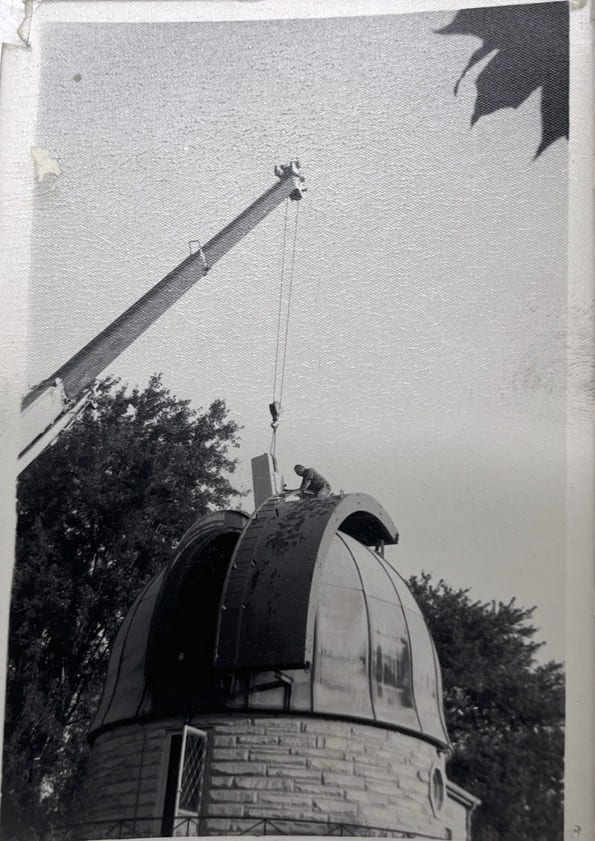

Meanwhile, David W. Latham, a graduate student at Harvard at the time, took matters into his own hands. He personally visited Bucyrus in late 1974 and submitted a proposal to cut costs down to a third the original estimate by doing everything in-house. Lee Loomis Jr.’s money was enough to cover the enterprise and Dr. Latham’s scheme was approved. He rented a truck and drove out to Ohio in 1975 and led the disassembly and installation of the telescope over the fall 1975 term.

By the next spring, everything was in place. The Loomis-Michael Observatory, named for the men who provided the telescope and the financial backing to install it, was formally commissioned with a wine-tasting star-gazing on Friday, March 5, 1976. Since then, it’s been a fixture of our campus!

Read Walter’s correspondence with the Science Center!

Read the first proposal for the telescope installation!

Read Dr. Latham’s report on the telescope and his updated proposal!

RSVP to the commissioning of the Loomis-Michael Observatory!

These pictures date to the disassembly and installation of the Michael Telescope in 1975!

Jump to Logbooks • Early History • A STAHR Is Born • Modern Day

The Observatory Before STAHR, 1976–1995

“A strange quiet lurks in the dome when there is no work to be done” –Mike Smart, 1978

STAHR did not exist when the Observatory was commissioned, and it would not exist for another two decades. The LMO’s primary purpose in the beginning was to be a teaching tool, the crown jewel of Harvard’s brand-new Science Center. It was run by a management team of undergraduate and graduate students as a direct extension of the Astronomy Department. Members of the management team were (as far as we can tell) appointed by the Astronomy Department and earned a small stipend in exchange for hosting open houses, teaching people to use the telescope, and arranging maintenance as needed. We know that astronomy classes at the time used the Observatory, but the specifics remain unknown to us. For now.

Back then, the telescope had a hand paddle (basically a remote control) and the plate camera (the large, wide tube on the side of the telescope) was routinely used to take photographic plates of the Moon, the planets, stars, galaxies, and more. Students were “inducted” into the telescope by their more experienced peers and taught how to use the instrument; access restrictions were looser at the time. On the bitterly cold night of November 2, 1976, a young Neil deGrasse Tyson became one of these inductees as Jupiter and a not-quite-full Moon grinned in the crystal-clear sky. He went on to spend many late nights

Observers were, for lack of a better term, generally more ambitious during the early years of the telescope’s history. At least one student recorded his campaign to spot every single planet (including Pluto!) and spent a logbook entry venting about his frustration with Mercury. Others honed their astronomy skills in the hunt to image every star in a given constellation, in attempts to view lunar eclipses, or in quests to find the many objects of the Messier Catalogue. As best we can tell, the Observatory was not so much a social space as a place of learning. Guided by astronomical almanacs and the trusty Michael Telescope, student astronomers tracked across the starry heavens and gained hands-on experience with astronomy. Much has changed since then and the role of the Observatory has evolved, but its mission remains: to connect the people of Harvard with the Universe.

Jump to Logbooks • Early History • Installation • Modern Day

The Origins of STAHR, 1995 – 2007

“Moon Party!!!” —An Unknown STAHR Officer, 2005

We are currently perusing the STAHRchives from this time period and collating our findings. Check back soon!

Jump to Logbooks • Early History • Installation • Before STAHR

Modern STAHR, 2007 – Present

“Screw it. We’re moving to Saturn and we’re taking the cats with us” —Ahmed Omran, 2018

This area is also under construction. Hard hats recommended.

Spring of 2007 marked the revival of STAHR after years of diminished activity. Led by large numbers of star-crazed students who apparently had too much free time on their hands, the organization bounced back and rushed to make up for lost time. Students organized stargazing trips to the Harvard Outing Club’s cabin in New Hampshire (the precursors to our modern Dark Sky Trips!) and increased the number of telescope classes from a few times a semester to a few times a week. STAHR witnessed the passage of Comet Holmes, observed a series of lunar eclipses, celebrated planetary alignments, and held as many Open Houses as we do now (if not more).

Some STAHR members during this time were especially crazy, and even organized events to see Shuttle launches from Cambridge! ISS flybys and a spy satellite falling out of orbit were also fixtures for the people of the time, and some students dabbled with giving each other presentations on cool astronomy-related subjects.

2008 was the last year of STAHR’s venerable sticker system. Certified telescope users once had stickers on their Harvard IDs that would allow them to borrow the physical Observatory key from the Science Center. It wasn’t perfect and evidently Harvard didn’t like it. After a few false starts, the Loomis-Michael Observatory switched to the modern swipe-based system after Thanksgiving 2008. This prompted chaos as the Board scrambled to make sure that people who had previously taken the telescope class could still access the Observatory; we think that everyone was successfully switched over, but it is quite possible that some lost souls were suddenly barred from the LMO by University fiat…

Observatory access saw another dramatic change in spring 2013. Prior to that point, the telescope classes had been a one-time commitment. 90-minute long sessions were organized on an ad-hoc basis over the STAHR mailing list and interested students were given spots first-come, first-served. Completing a single one of these classes earned one a sticker (or, after 2008, swipe access) and entitled them to use the Observatory. In 2013, that changed to the modern regime of three 90-minute classes and a test-out session.