In her formative years, the American poet Emily Dickinson’s interests centered on the study of voice and especially piano, for which she displayed considerable accomplishment and ambition. Her correspondence supplies the background for these activities while the contents of her music book provides a revealing perspective on just how assiduously and enthusiastically she collected, listened to, and performed the music of her time.

Music books or “binders’ volumes” were extremely popular during the years 1830-1870. These personal collections of bound published sheet-music titles were assembled by young women primarily during their adolescent years, when musical training and accomplishment was sought after as a reflection of cultural refinement and gentility.1

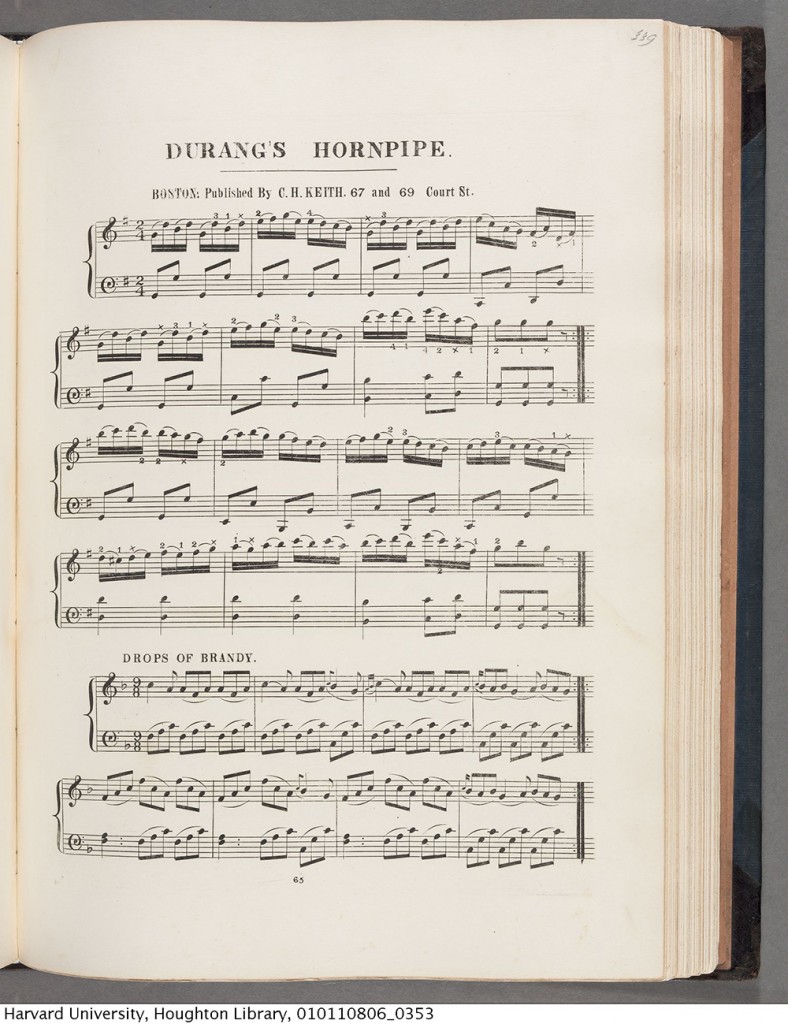

The music in Emily Dickinson’s binders’ book was collected over a period of about eight years, from 1844–52. Of the sheet music titles in the Dickinson book, 35 percent contain a year of copyright. Another 30 percent can be dated by the plate numbers often included at the bottom of each page of music, used by music publishers to identify and collate their yearly inventory.2 Nearly one third of the Dickinson music book’s content spans the years 1843–45, an active period of musical study for Dickinson (ages 12–14).

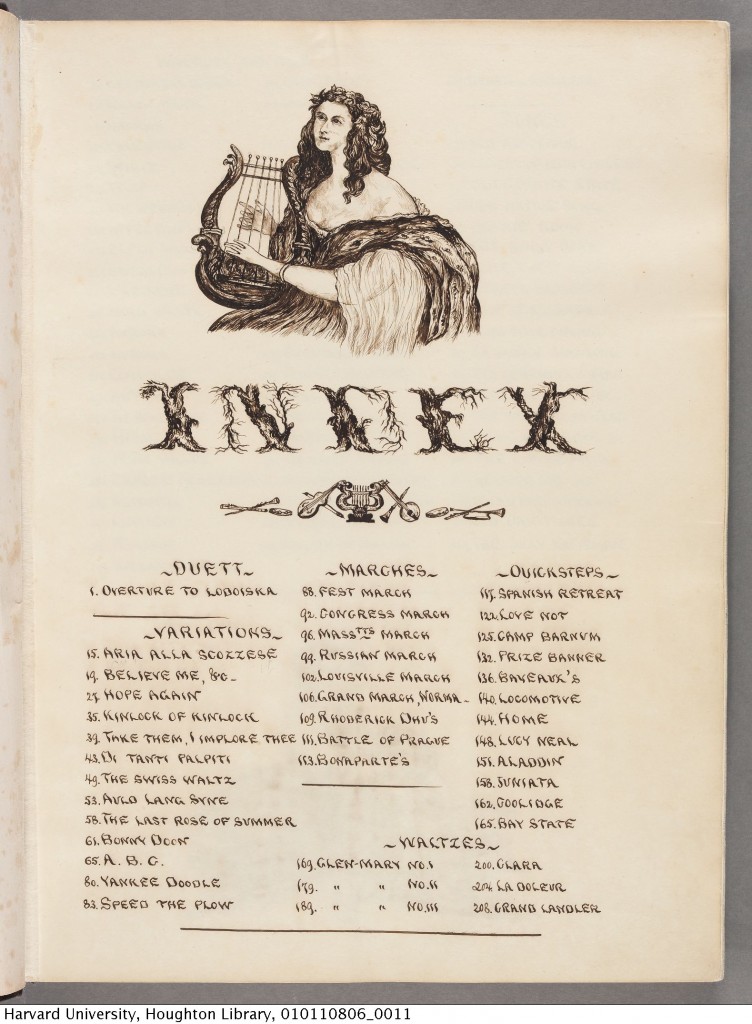

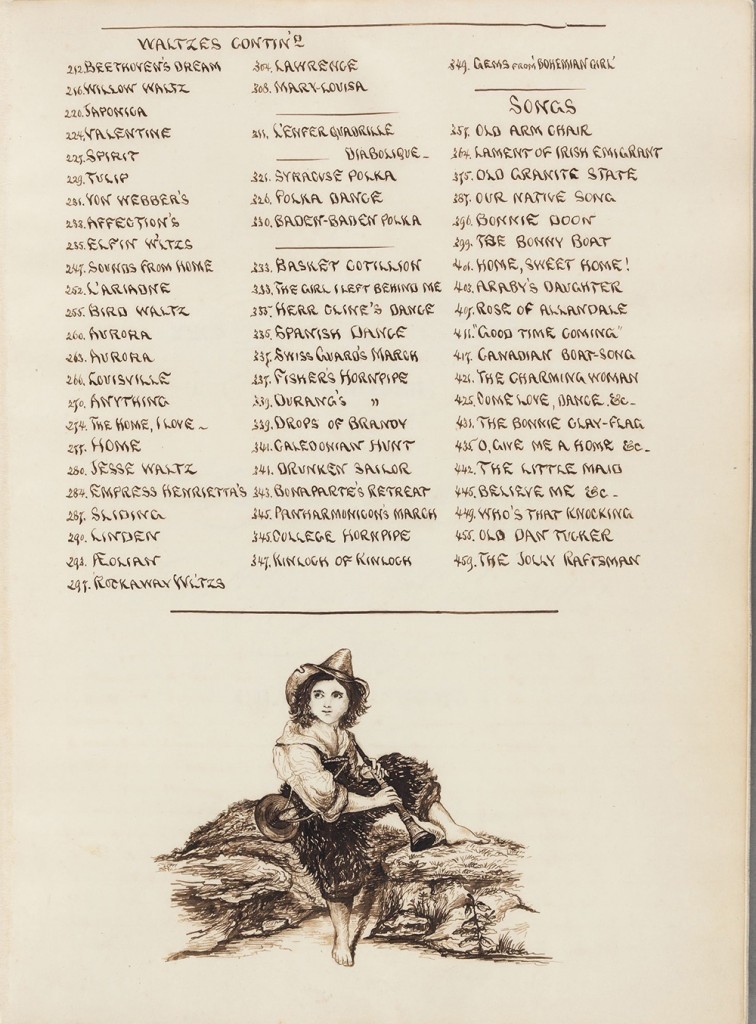

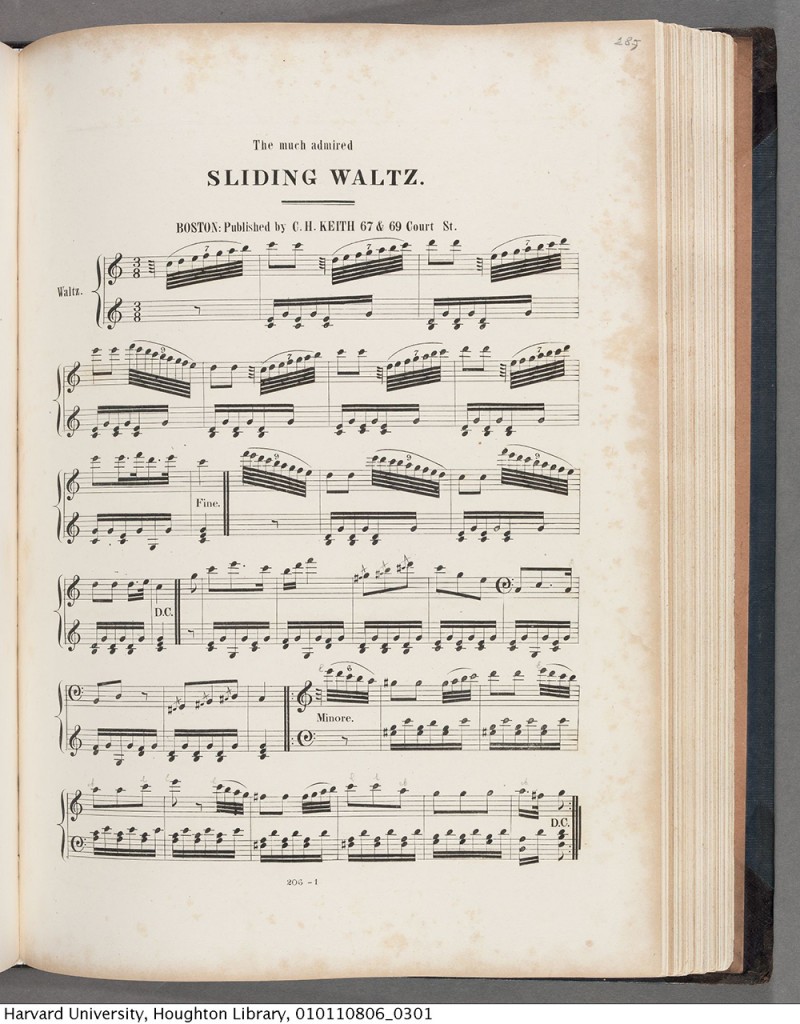

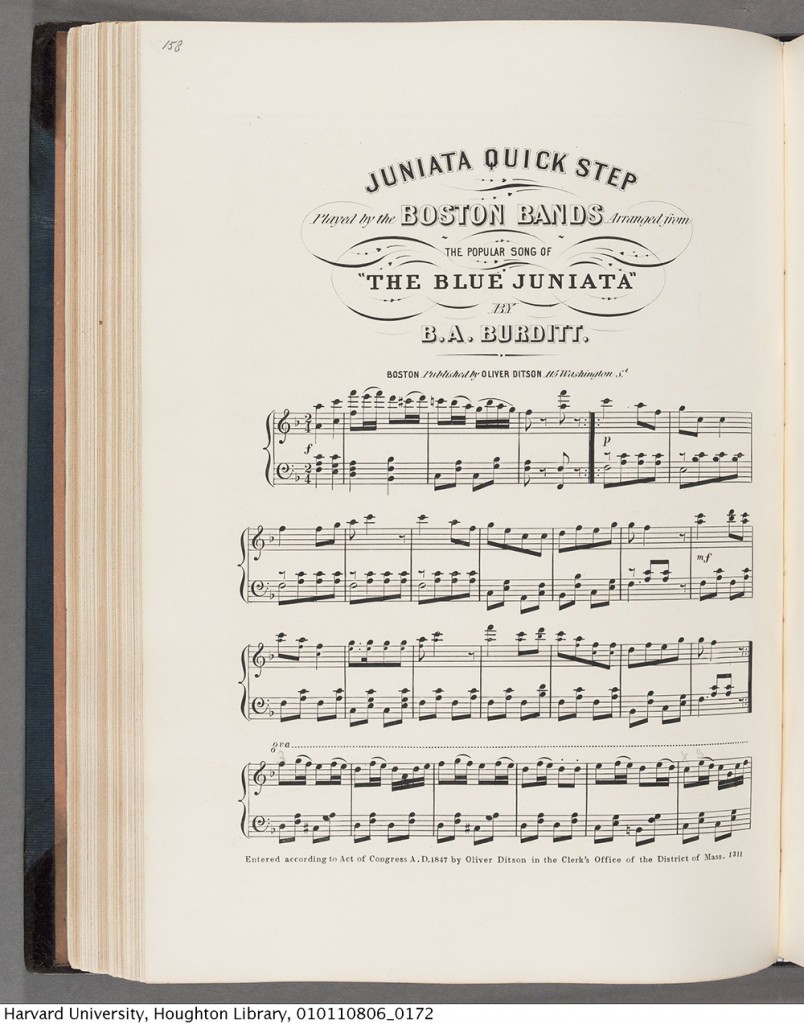

The average binder’s volume contains 35 to 45 pieces of music. At just over 100 pieces, Emily Dickinson’s music book is uncommonly large. The book’s content tells us a great deal about her musical interests. Most binders from the period contain a majority of vocal music and only some instrumental numbers. In contrast, eighty percent of the Dickinson book is devoted to instrumental music, indicating Emily’s keen engagement in the piano repertoire of her day.

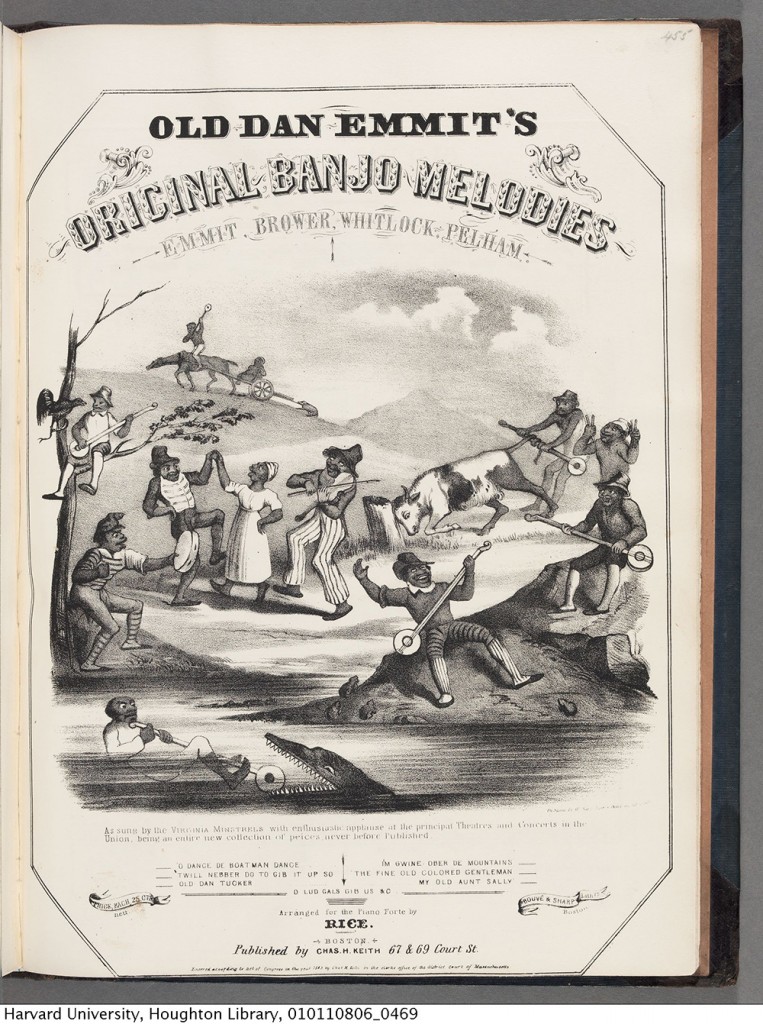

While the music book contains a majority of popular waltzes, marches, quicksteps, theme and variations, and instrumental operatic arrangements, many of considerable difficulty, there are also notable groupings of traditional Irish and Scottish dance tunes and ballads, political songs, and in particular, minstrel music which are rare in binders’ volumes.

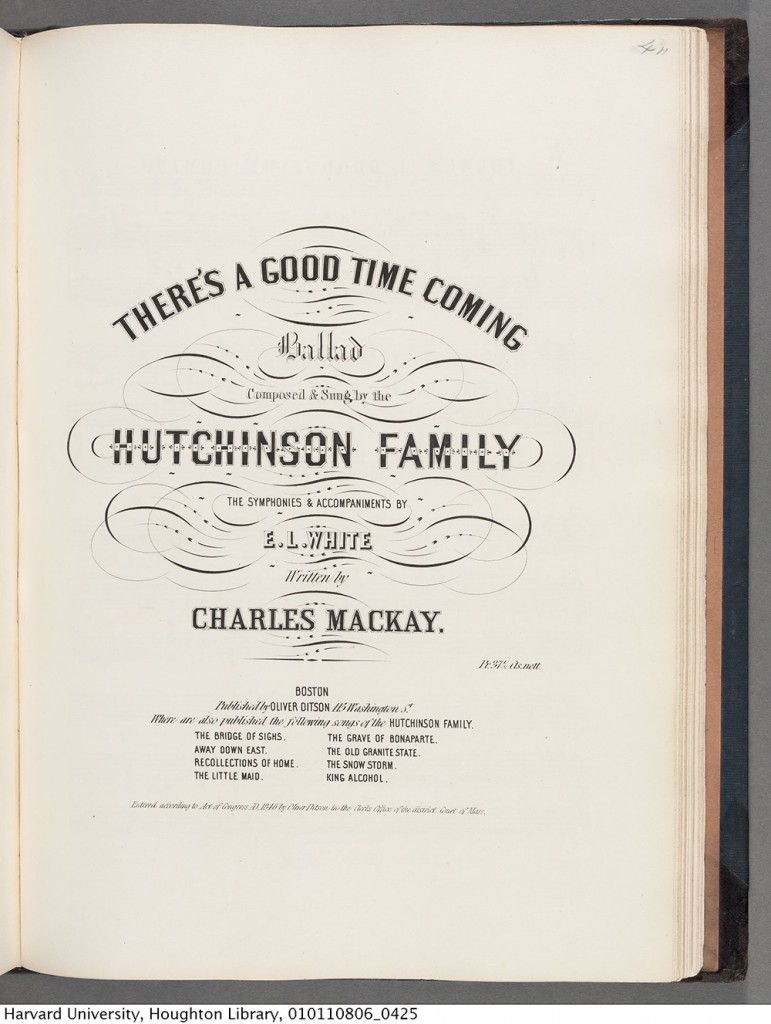

Among the pieces in the music book mentioned by Dickinson in her correspondence are “The Last Rose of Summer,” “Sounds from Home” by Josef Gung’l, and “There’s a Good Time Coming” by the Hutchinson Family.

With the digitization of Emily Dickinson’s music book there is indeed a good time coming, as a fuller picture emerges and a new twenty-first century light now illuminates the musical activities of America’s most beloved poet.

Thanks to George Boziwick for contributing this post. George Boziwick is Chief of the Music Division of The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center. He is also a composer, performer and co-founder of the Red Skies Music Ensemble whose mission is to make archives and special collections come alive through research and performance (redskiesmusic.com). The ensemble has presented a lecture/performance on the Dickinson music book, “The Musical Parlor of Emily Dickinson” at The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, and in Amherst MA, sponsored by the Emily Dickinson Museum. A paper on the music book was presented by George Boziwick at the 2013 International Association of Music Libraries conference in Vienna.

1. Meyer Frazier, Petra, American Women’s Roles in Domestic Music-making as Revealed in Parlor Song, Ph.D. diss., University of Colorado, 1999, 7–22, 44–72, 87–94, 175–200.

2. D.W. Krummel, Guide for Dating Early Published Music: A Manual for Bibliographic Practices. (Hackensack, NJ: Joseph Boonin, Inc., and Kassel: Barenreiter Verlag, 1974) 229–240.