By Peter X. Accardo, Scholarly and Public Programs Librarian

As part of our observance of African American history month, Houghton Library has taken an opportunity to research and reflect on the life and work of the library’s first African American colleague, Harold M. Terrell, Jr. At a time when the Harvard College Library employed very few African Americans, Harold was a notable exception in a career that spanned six decades. This post is intended to honor him and to highlight the lasting contributions he made to the library.

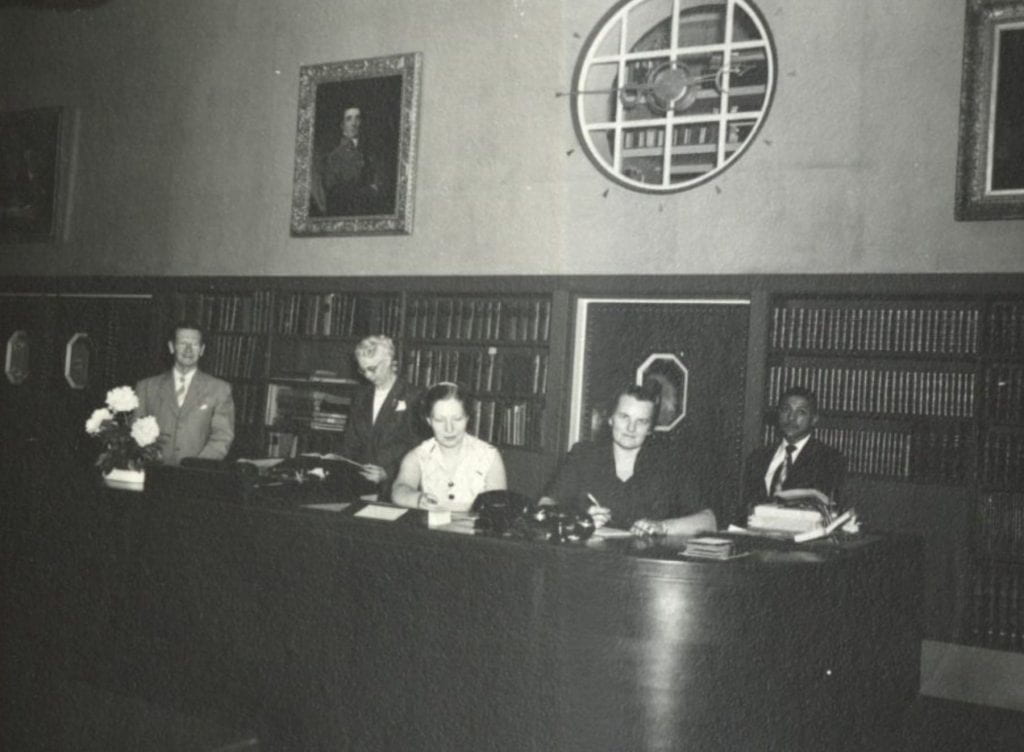

Harold was born in Boston on 20 June 1929, the youngest son of Harold and Mary (Forbes) Terrell. His father had moved in 1920 from North Carolina to Boston, where he held several jobs through the Great Depression and the Second World War; his mother raised their three children at home. Young Harold attended public schools, graduating from Roxbury Memorial High School in 1947. Two years later he joined the staff of Houghton Library as an assistant in the library’s reading room; a photograph of reading room staff taken in the early 1950s shows Harold as a young man, sporting the fine pencil mustache he wore his entire life.

After serving his country during the Korean War, Harold transferred to the Houghton catalog department as a typist. In this role he distinguished himself by delivering accuracy where it most mattered: in the card catalogs of library collections then consulted by the scholarly public. From his desk on the Houghton mezzanine, he developed an extraordinary ability to decipher the handwriting of rare book catalogers who supplied him with their bibliographic worksheets, the lifeblood of his work. He mastered the orthographic conventions of most Western European languages, so much so that his proofreader’s red pencil was seldom lifted.

Harold’s typed cards were photomechanically reproduced in multiples for distribution in the library’s date of publication file, place of publication file, and official shelf list; other copies were carefully interfiled in the Union Catalog housed in Widener Library. Harold also produced brief bibliographic records on 3-part carbonless duplicate slips for incoming accessions that awaited full cataloging. He brought the same scrupulous attention to detail in his work as the department’s end-processor, responsible for typing shelf tabs and affixing bookplates and labels into the thousands of books that passed through his hands. To the general public, his activities were little known or understood, but they were essential to the effective functioning of a special collections library.

In the 1980s Harold’s cards found a new purpose when a set was sent to a team of bibliographers working on the Eighteenth-Century Short Title Catalog (ESTC), then in its development phase and which over time has become an indispensable digital resource for eighteenth-century studies. The ESTC bibliographers would annotate and return bundles of cards, in order to confirm the existence of a comma in a book’s title or whether an errata leaf was present in the Houghton copy. Ultimately, online cataloging and online public access catalogs (OPACs) brought about the demise of traditional card catalogs. But it was Harold’s cards that allowed other Houghton staff to devise the retrospective conversion projects that made possible the “digital turn” away from card catalogs toward HOLLIS: now his work became their life blood. The library partnered with University Microfilms International to undertake a major project to preserve the learned content of the old catalog on microfiche. To this day the microfiche is kept in the Houghton Reading Room, where it is consulted by staff and visiting bibliographers: turn on the fiche reader lamp and it is largely Harold’s cards that are illuminated, preserving for posterity the expertise of Houghton’s cataloging staff.

Several former colleagues remember details related to Harold that speak to his character and his quirks. “Harold had a bounce in his steps and moved quickly,” one reminisced: “His hands, above all, moved on the typewriter with the speed of lightning. I remember a ring – high school ring I believe – on the fourth or fifth finger of one of his amazing hands.” Sometime in the 1970s, Harold was presented with an IBM Correcting Selectric II typewriter, though it was only on rare occasions that he engaged the highly touted, self-correcting feature. The staccato of Harold’s typing became the mezzanine’s soundtrack for more than a generation.

Another colleague remembers Harold’s fondness for a straight-back aluminum chair, which she regarded as his “throne.” On occasion, a staff member would remove his throne for use by musicians who took part in the library’s chamber music series. If the throne was not promptly restored to the mezzanine by 9 AM the next day, the king was not amused. Another staff member recalls that Harold “had an extra dry sense of humor that you could only glean from the subtlety of his facial expressions.” You could expect a “well-executed eye roll” when he witnessed or overheard colleagues disputing the finer points of rare book cataloging or when an intruder trespassed his inner sanctum.

Shy and self-effacing, Harold still managed to bring his elegant sense of style to the library. He arrived each morning promptly, and impeccably dressed: jacket, pressed Oxford shirt (short sleeve in summer) and tie. Harold rarely took a sick day. He looked forward to occasional long weekends in Montreal, and in August, he met up with friends for extended and well-deserved stays at Oak Bluffs on Martha’s Vineyard.

By the time he announced his intention to retire in 1994, Harold had accumulated many weeks of unspent vacation and sick time. True to type, he neatly filled out a stack of blue time slips, noting upon the last: “End of 45 years of service!!!” Well-wishing colleagues presented him with a navy blazer from Brooks Brothers. Sadly, only a few years remained for Harold to enjoy the company of his older brother Joseph and younger sister Gertrude (Terrell) Townsend (who had gained distinction in 1968 as a teacher at the first Montessori School in Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood), along with his devoted nephews, nieces, and friends. While not widely recognized in his lifetime for his achievements, when Harold M. Terrell, Jr. died on 29 November 2000 he left an impressive record of exacting work, which continues to emanate in a digital guise from thousands of online bibliographic records in HOLLIS.

I wish to thank my Houghton colleagues, past and present, for sharing their memories of Harold Terrell: Anne Anninger, Vicki Denby, Cindi Naylor, Nancy Reinhardt, Janet Scinto, Golda Steinberg, Roger Stoddard, and Melanie Wisner.