This post is part of an ongoing series featuring items from the newly acquired Julio Mario Santo Domingo Collection.

Frans Balthazar Solvyns was born in Antwerp in 1760 and for the early part of his career was a marine painter capturing the likenesses of ships, ports, and harbor views on canvas. He departed for Calcutta in the 1790s where he then worked as a journeyman artist working for the upper-middle class restoring works of art, decorating carriages, and other pursuits. He traveled during this time throughout the Indian subcontinent and came up with the idea to create a series of etchings documenting the inhabitants. The etchings covered professions, castes, typical dress, transportation, and festivals to name just a few. The original etchings were published in 1796 in A Collection of Two Hundred and Fifty Coloured Etchings: Descriptive of the Manners, Customs and Dresses of the Hindoos in Calcutta. It was a financial failure probably due to artistic tastes of the time which were said to find the color of the etchings too somber and monotonous. However they did appeal to the London publisher Edward Orne who published a pirated version without the permission of Solvyns. Orne’s version was mainly dedicated to the costumes or modes of dress and the plates were redesigned in warmer colors. Our particular volume is one of Orne’s pirated editions published in 1807 titled The costume of Hindostan, elucidated by sixty coloured engravings with descriptions in English and French, taken in the years 1798 and 1799. Here are a few of the plates that I found particularly interesting.

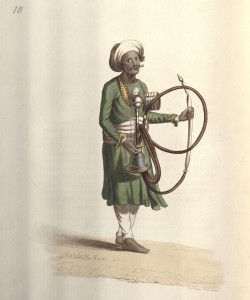

A Hooka-Burdar or Hooka Purveyor was responsible for making the chillum, or pipe, keeping the hookah in order and attending the master whenever they were dining. The hookah itself could be made in various materials and adorned according to the wealth of the owner. Often it was covered with precious jewels such as rubies, diamonds, or emeralds and the base was most commonly made out of silver, gold, metal, or glass.

A Hooka-Burdar or Hooka Purveyor was responsible for making the chillum, or pipe, keeping the hookah in order and attending the master whenever they were dining. The hookah itself could be made in various materials and adorned according to the wealth of the owner. Often it was covered with precious jewels such as rubies, diamonds, or emeralds and the base was most commonly made out of silver, gold, metal, or glass.

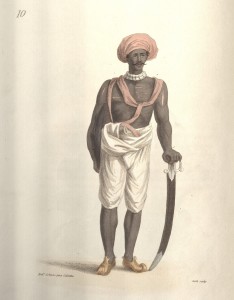

A Syce or Groom was described as being assigned to a single horse who would then run next to said horse and when they stopped he would secure the horse’s head with his rope. In his hand you will see a piece of horsehair that is attached to a piece of wood with which he would be tasked with preventing the flies from “fretting the horse.”

A Syce or Groom was described as being assigned to a single horse who would then run next to said horse and when they stopped he would secure the horse’s head with his rope. In his hand you will see a piece of horsehair that is attached to a piece of wood with which he would be tasked with preventing the flies from “fretting the horse.”

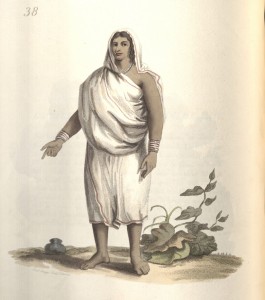

This woman’s status is simply identified as a Woman of Inferior Rank. The description that goes with the plate reveals other details about women in general stating that when a woman is widowed she is no longer allowed to wear colors on the border of her clothes nor ornaments, except for a necklace made of wooden beads, her head is shaved, and she becomes a virtual servant in her household. According to the Hindoo laws she is unable to marry again and by subduing her passions and attraction she is reduced to a state of servility. The author helpfully reveals the difference for European women by stating “Happily this odious interdiction, and not less odious custom are unknown to the fair daughters of Europe, who are unrestrained in the exercise of their charms and are ever free to confer those blessings that constitute the happiness of men.” Since this particular plate has none of these characteristics as her dress has a color border, she is wearing jewelry, and head is not shaved, I have to conclude this is just a woman of inferior rank but not a widow.

This woman’s status is simply identified as a Woman of Inferior Rank. The description that goes with the plate reveals other details about women in general stating that when a woman is widowed she is no longer allowed to wear colors on the border of her clothes nor ornaments, except for a necklace made of wooden beads, her head is shaved, and she becomes a virtual servant in her household. According to the Hindoo laws she is unable to marry again and by subduing her passions and attraction she is reduced to a state of servility. The author helpfully reveals the difference for European women by stating “Happily this odious interdiction, and not less odious custom are unknown to the fair daughters of Europe, who are unrestrained in the exercise of their charms and are ever free to confer those blessings that constitute the happiness of men.” Since this particular plate has none of these characteristics as her dress has a color border, she is wearing jewelry, and head is not shaved, I have to conclude this is just a woman of inferior rank but not a widow.

The costume of Hindostan, elucidated by sixty coloured engravings with descriptions in English and French, taken in the years 1798 and 1799. By Balt. Solvyns. London, E. Orme, 1807. GT 1460.S6 1807 F can be found at the Fine Arts Library.

Thanks to Alison Harris, Julio Mario Santo Domingo Project Manager for contributing this post.