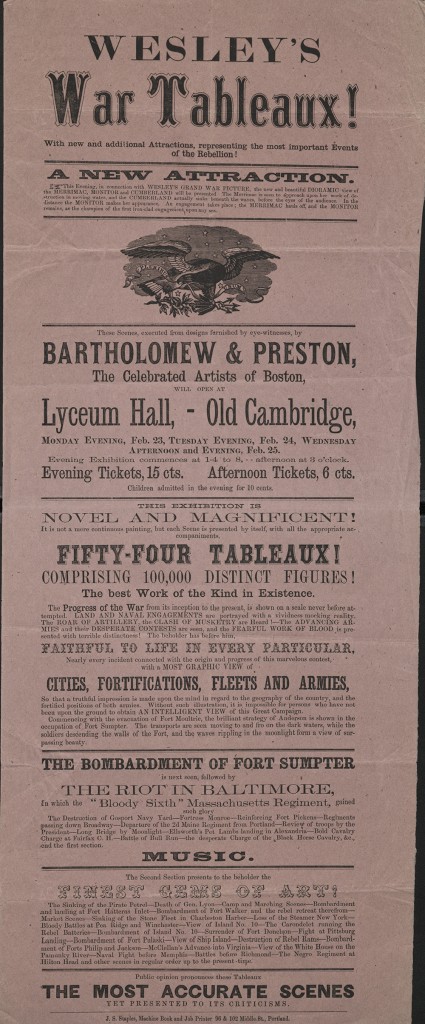

While cataloging American Civil War broadsides, I found this playbill advertising Wesley’s War Tableaux, to be presented in Cambridge, Massachusetts at the Lyceum Hall from February 23-25 [1863]. Moving panoramas were large painted scenes on rolls of canvas, framed by a proscenium to hide the mechanism; they were unwound from one roll to another, to create the illusion of movement and the progression of time, and were often accompanied by music. They became popular public spectacles in the early to mid- 19th century, with touring productions traveling around Europe and America; toy moving panoramas were produced for the home. Subjects included exotic locales, historical events and elaborate rural and urban scenes, such as Henry Lewis’ remarkable Mississippi River panorama. Dioramas included additional figures for a more three-dimensional effect.

The diorama for this spectacle was designed by Truman C. Bartholomew and Preston Wesley. Bartholomew was a scenic artist of note in Boston; in addition to providing scenery for Boston theatres, he produced a Bunker Hill panorama in 1838, and other moving panoramas between 1848 and 1863, depicting such scenes as the Battle of Lexington, a tour of Scotland, and the Kennebec River. In 1857, with a partner, Chase, he created a three-dimensional “mechanical mirror” of naval battles of the War of 1812, “with 7,000 moving figures in six separate scenes.” [1]

This production, also known as Wesley’s Grand War Picture, has been enhanced with a new attraction: “Dioramic view of the Merrimac, Monitor and Cumberland … the Merrimac is seen to approach upon her work of destruction in moving water, and the Cumberland actually sinks beneath the waves, before the eyes of the audience.” Other tableaux featured Army battles, the Baltimore Riot featuring the “Bloody Sixth” of Massachusetts, the attack on Fort Sumter; and also “The Negro Regiment at Hilton Head and other scenes in regular order up to the present time,” probably the company of former slaves that became the First South Carolina Volunteers.

The playbill proclaims: “Land and naval engagements are portrayed with a vividness mocking reality. The roar of artillery, the clash of musketry are heard! The advancing armies and their desperate contests are seen, and the fearful work of blood is presented with terrible distinctness!” This sensationalism probably elicited a strong reaction in the spectator; local regiments were still engaged, and the terrible battles of Antietam and Fredericksburg were only months past. For more background on panoramas, dioramas and cycloramas, see the Harvard Fine Arts Library’s copy of Illusions in motion: media archaeology of the moving panorama and related spectacles by Erkki Huhtamo (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2013).

[1] Arrington, Joseph Earl. “Lewis and Bartholomew’s Mechanical Panorama of the Battle of Bunker Hill.” Old-Time New England (Fall 1961, vol. 52, no. 186): 50-58. Web. 4 March 2015.

Portland [Maine] : J. S. Staples, printer, [1863?]. US 102.8.5 (27).

Thanks to cataloging assistant Dana Gee for contributing this post.