Reframing Opioid Addiction Treatment: What is harm reduction all about?

by Lauren Granata

figures by Xiaomeng Han

As Covid-19-related deaths overwhelmed the country in 2020, drug overdose deaths furtively took their own toll. The opioid epidemic is still surging, but a new Rhode Island law aims to combat the problem through harm reduction. Instead of fixating on sobriety-centered treatment, the primary function of the new law is to protect people from infection and overdose.

What are opioids?

Pain is a normal part of the human experience that helps us navigate the world safely. Since the 1600s, doctors have been using pain-relieving medications to make patients more comfortable while being treated. When you have a headache, you likely reach for an over-the-counter painkiller like Ibuprofen, which treats pain by reducing inflammation. For more severe pain or chronic conditions, doctors may prescribe a narcotic like codeine, morphine, oxycodone, or fentanyl.

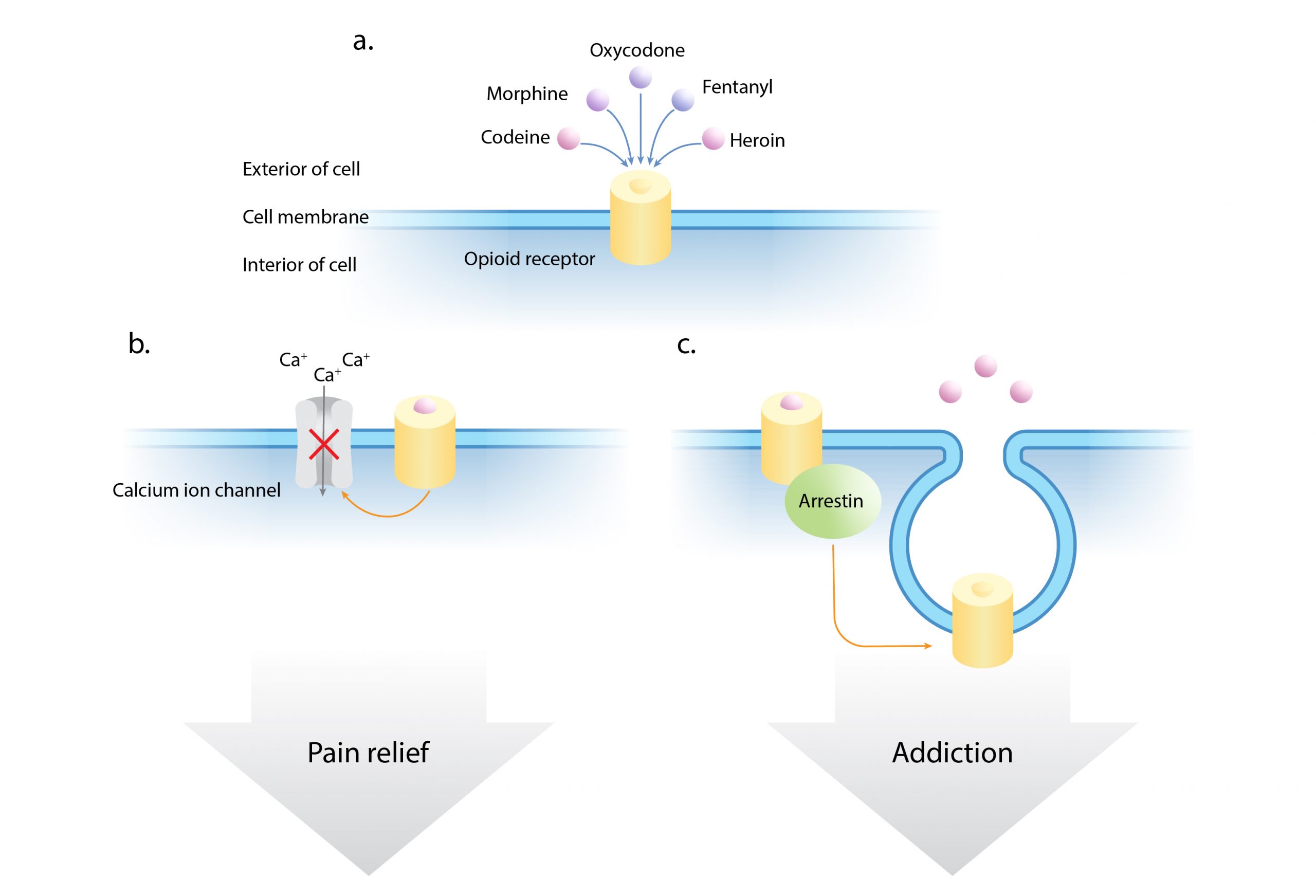

Opioids are a specific class of narcotics that block pain by binding to proteins called opioid receptors that decorate the surface of cells in the brain and throughout the body. Opioid narcotics are derived from opium, the natural compound found in the poppy plant. Codeine, morphine, and oxycodone come from slightly modified versions of opium, while fentanyl is a highly potent synthetic derivative. Heroin is made from morphine and is often diluted with other substances when distributed.

When any of these substances activate opioid receptors, it sparks a cascade of responses from messenger proteins inside the brain cell, or neuron, which change the way the cell behaves (Figure 1). For a neuron to fire and send a pain signal, enough calcium needs to enter the cell through specific passageways that open just for calcium particles. Activated opioid receptors trigger a message to close these passageways, making it more difficult for calcium to pass through. This blocks pain signals from being transmitted while also slowing the heart and acting as a sedative.

Opioids become addictive because of the natural negative feedback loop that begins from the first experience of taking a drug. When opioids bind to their receptors, the cell begins to engulf these proteins and bring them into the cell. This removal of receptors from the cell surface is facilitated by a class of proteins known as arrestins. With fewer receptors available for opioids to attach to, the cell is less sensitive to the unbound opioids floating around the external space. Thus, more and more opioids are needed to achieve the same pain relief. Continuously increasing tolerance to a drug in this way is the basis for opioid addiction.

The shift to harm reduction

In light of the opioid epidemic, some cities have attempted to open centers for supervised drug consumption where people can use their personally obtained drugs under medical supervision. Rhode Island is the first state to allow such “harm reduction centers” (HRCs). In the push for harm reduction-based approaches to treating drug addiction, the legalization of HRCs in any state is a milestone.

Harm reduction challenges our society to think beyond the stigmas assigned to people suffering from opioid use disorder. As a society, we are eager to applaud the successful sobriety stories, and we can commemorate those who lost their lives to addiction, but we ignore all of the people who are still addicted but want to recover. By failing to protect this group, people will continue to use illegal drugs, risking their lives each time. Although achieving lifelong sobriety is possible, it is an arduous journey, and most people seeking rehabilitation will relapse at least once.

Amy Godwin knows this all too well. After losing her 24-year-old daughter to a fatal overdose in 2020, she wishes that more resources would have been available outside of formal treatment. Godwin felt helpless during the period she called “the treatment shuffle” as she watched her daughter cycle through treatment centers after periods of sobriety and relapse. She agrees that with more places like HRCs for people to turn, the chance of overdosing would be greatly reduced, and more people might be saved.

Harm reduction has recently been gaining attention, but it is not a new concept. Some harm reduction practices have been operating for almost 60 years. Methadone maintenance programs, first developed in 1964, help to reduce heroin cravings and circumvent severe withdrawal symptoms. They continue to be a mainstay of detoxification and long-term sobriety plans. Since their inception in 1988, syringe exchange programs have likewise become standard as mounting evidence supports their effectiveness in reducing HIV and hepatitis outbreaks. HRCs will add to these efforts by joining together multiple safety-centered services in one setting. They address the immediate concern of keeping people alive while also supporting the ultimate goal of providing a clear entrance to long-term treatment.

HRC personnel will test drugs for synthetic opioids like fentanyl, which surpassed heroin and prescription opioids as the most prevalent cause of overdose deaths in 2016 and steadily continues to take more lives each year. Staff will also be equipped with naloxone (Narcan), the life-saving overdose reversal drug. Most importantly, providers will be able to connect users with the appropriate resources, like methadone clinics or residential treatment, should they request them.

Rhode Island State Senator Joshua Miller, the bill’s sponsor, stated that supervised consumption will also be “a gateway to long-term treatment”. Reports from Canada, where safe consumption facilities have been operating since 2003, support Sen. Miller’s prediction. There, people who began regularly using the facilities were over 30% more likely to initiate detoxification and additional treatment in the future.

HRCs are not cheap, but in the end, they will save money. A study from the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review projected the cost of running supervised consumption facilities versus syringe exchange programs alone (Figure 2). HRCs are predicted to save an annual $4.5M in a simulation calculated for the city of Boston. Although the operating costs of HRCs are higher than syringe service programs alone, overdose prevention is expected to result in fewer ambulance rides, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations, ultimately saving both lives and money.

Obstacles facing harm reduction centers

Although the evidence suggests promise, reaching the success projected by these models and envisioned by Sen. Miller will not come without obstacles.

One obstacle facing HRCs is persuading people to use the facilities. “Addicts look for isolation, not community,” says CB, a Rhode Island native currently in recovery from opioid use. But he does see value in the concept. “You can at least make sure no one overdoses and make sure everyone can get Narcan, and that will definitely save lives,” CB says. He suggested creative approaches to incentivizing supervised consumption at HRCs, such as involving those who would willingly seek out harm reduction services to encourage safer practices within their circles.

Another barrier is the perception that HRCs might encourage even more drug use. Sen. Miller urged that a simple change in language from the traditional term “safe injection facility” to “harm reduction center” may help to reinforce the public’s understanding that supervised consumption is just one component of the overall mission of HRCs. Ultimately, changing the public’s opinion will be a matter of convincing them that people suffering from drug use disorders deserve to live.

Overcoming legal hurdles and societal opposition, Rhode Island is leading the way towards widespread acceptance of harm reduction by making a potentially groundbreaking shift in effective interventions for addiction. Careful consideration will be needed to operate the facilities in a way that will effectively serve the community and encourage their use. The success of similar programs outside of the U.S. shows that HRCs hold promise for curbing opioid-related overdoses and improving the quality of life for people who use them.

Lauren Granata is a PhD student studying stress and brain development. She is also a staff writer and producer for the Science Rehashed podcast, where she’s covered episodes on bullying in academia and the neuroscience of computer coding.

Xiaomeng Han is a graduate student in the Harvard Ph.D. Program in Neuroscience. She uses correlated light and electron microscopy to study neuronal connectivity.

Cover image by Jukka Niittymaa from Pixabay.

This piece was published in partnership with the NPR Scicommers Program.

For more information:

- To learn more about how opioids work, see this 2-Minute Neuroscience video

- To read more about the origins of the opioid epidemic, check out this Nature article

- For more information about the harm reduction movement, visit harmreduction.org