Multitasking with Clouds [16 Seconds]

I board the train from New York to Boston in the most efficient manner. There are no farewell scenes on the platform; no teary-eyed lovers cling to each other one last time, knowing that they won’t see each other again any time soon. The train is late and already full. The only free place I find is next to a woman with a cell phone watching a DVD on her PC.

My neighbor is pleasant but not talkative. She never looks out the window. When she sees me taking out my photo camera, she smiles with friendly condescension: “When I first came to New York, I also took pictures.” My foreign accent betrays me but also allows me a refuge. Otherwise I would have been embarrassed to look outside at the last embers of sunrise dying over the New York skyline.

For better or for worse, panoramas are dying a slow death, yielding to interfaces and cell phone screens. Once they reigned supreme, framing the rivalry of art, technology, and nature. The word “panorama,” from the Greek pan (“all”) horama (“view”), all-encompassing vision, was coined by the Scottish painter Robert Barker in 1792. He built the first panorama house in the world especially for his grand wide-angle paintings of the city made on large cylindrical surfaces. The panorama became an all-encompassing fashion, making its inventor rich and famous. Since then all kinds of “oramas” have proliferated—from cosmoramas to lifeoramas in the nineteenth century to the full-immersion “Cinerama” shown in Universal Studios tours, a forerunner of modern IMAX film-projection technology.

The nineteenth century was the age of panoramas. Daguerre began as a panorama artist and invented photography only after a fire had destroyed his panorama house. Art and technology competed in the public imagination of the new space of modernity. Photography was the next step in the game of illusions. Soon afterward, the train journey became a part of “panoramania” and framed many real-life panoramas. It was never merely about arriving at a destination but also about window-travel. Many works of nineteenth-century literature are framed by the train journey. Its unhurried rhythm inspired strangers to unburden themselves, to think about the meaning of life. We remember how one famous passenger confessed to his accidental neighbor that he might have killed his wife over a Beethoven sonata. And another unfortunate heroine found her end under the wheels of a train, as if punished by the writer himself. Panoramas became victims of their own success and in a peculiar reversal of fortune, from a painting of a landscape they began to refer to the landscape itself. Now when we speak of a “panorama,” we mean nature (often at its most scenic), not the now-obsolete panorama art. Panoramas occupied the space of play between nature and art, and besides the dream of the grand illusion and all-encompassing perspective, they also revealed a horizon of finitude, the limit of human vision. The painter of panoramas strived to create a life-like illusion, always aware of its impossibility. Painting “en plein air” was like trying to square a circle and dwelling on its elusive curves.

From painted panoramas to photographic exposures, from real to fictional train journeys, the road led to the discovery of cinema, which was imagined in a novella by Villiers de L’Isle-Adam, The Future Eve, some fifteen years prior to the technological invention. Cinema would borrow the language of panorama (“panning” and “panoramic shots”), and movie houses shared architectural features with old panorama houses and train stations.

The early twentieth century became the age of cinema, which continued its own train travel from the first film by the brothers Lumiere, The Arrival of the Train, to Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera. The latter film’s hero challenged “bourgeois realism” and jumped on the train tracks, this time not to kill himself but to expand human vision with an under-the-wheels panorama. In a more conventional fashion, many a romance was happily consummated with a train driving into a tunnel and the cheerful words The End written over it.

Yet much of the early cinema was non-narrative. The brothers Lumiere’s “archaic” proto-documentary The Arrival of the Train featured non-centered frames with actions taking place chaotically and spontaneously in different parts of the image. This kind of cinema was about narrativity itself and its euphoric potentialities. It allowed the spectator a narrative freedom to play with unpredictable adventures and roads not taken. It depended neither on formulaic plots that would dominate cinema with the introduction of the Hollywood code in the 1930s nor on the carefully calculated interactivity of the new gadgetology.

The industrial landscape was the contemporary of cinema’s golden years. Factories would give jobs to immigrants, and rails would transport them. Rails, not roots, were what mattered. Rails should not turn into roots. Otherwise they bind you to the soil and never let you go. Cinema celebrated industrial construction but also revolutionary destruction, often simultaneously. Thus in the films of Sergei Eisenstein, especially in October, the old monuments would become ruins only to be transformed into new monuments that used some of the same reconstruction and retouching as the old ones.

Later twentieth-century visual art stopped trusting the enlarged renaissance perspective of the panoramas, turning to a more self-reflective and ironic conceptual perspective. It explored virtuality in its original sense, as imagined by Henri Bergson, not Bill Gates. It was the virtuality of human consciousness and creative imagination that evades technological predictability. Yet much of conceptual art was still haunted by the horizon of finitude, a certain clouded existential panorama; whether it acknowledged it explicitly or evaded the question is another matter.

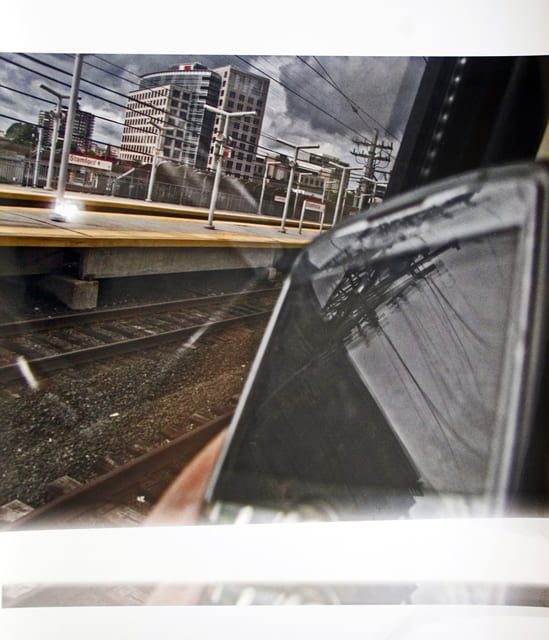

In the early twenty-first century, Netscape took over the landscape. Just as the word “mail” turned into the retronym “snail mail,” the word “window” will soon become “snail train window.” Microsoft Windows offers faster and more exciting panoramas than the “snail train windows” of the malfunctioning and underfunded Amtrak service.

My neighbor on the train needs neither snail window watching nor snail talking with a stranger. She is happily interfacing in private. In a world of endless pop-up windows, horizons and limitations will be abolished. All you need is better tech and death itself will become a thing of the past. And, to paraphrase Faulkner, the past will never be dead again, it won’t even be the past.

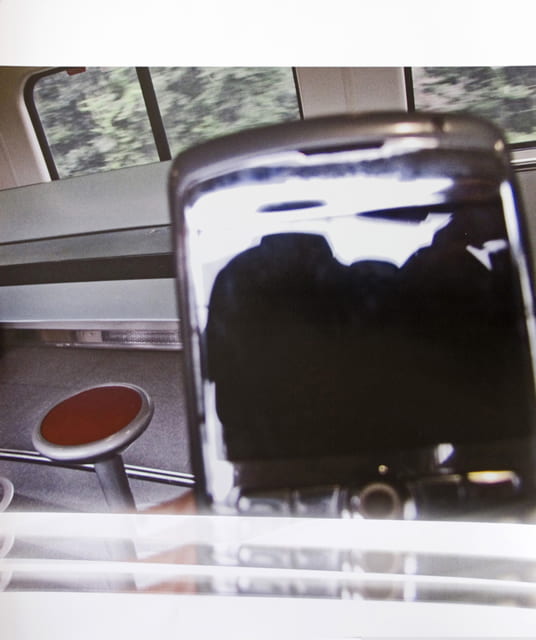

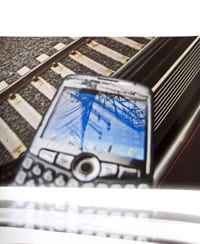

Furtively I look out at the landscape of industrial decay, ruins of former factory towns, framed by endless pipes and wires. From a certain uncomfortable angle, the digital screen turns into an old-fashioned reflective surface shamelessly invaded by passing clouds and sunset panoramas. The computer is only a material thing, after all, however light it is. I am perched on the edge of my seat trying to commemorate the flickering shadows on my neighbor’s computer screen without disturbing her cinematic pleasures. I feel like a private detective spying on transience itself. At some point in the DVD movie a murder happens and the dying man screams for help in the middle of the clouds and trees.

Is there a corpse there or just another ill-shaped cloud?

Multiburst does not allow for blow-ups and zooms. It resembles the “primitive cinema” of the early twentieth century. I cannot rewind it either, for the clouds and shadows would never conspire in the same way.

The twilight time is short, the DVD movie is almost over and so is the time of panorama watching.

My “Chicken Sierra Special” purchased in the café car is getting cold. The “Sierra” part of it, a sun-dried tomato smashed into the Wonder Bread, has an aftertaste of another time.

“Dad, is the moon moving?” asks a little boy behind me.

“No, it’s very far away,” the father explains. “It’s us who are moving…”

I smile and turn around.

“What’s your name?” I ask the boy.

“I forgot,” he answers.

The windows are dark now, turning into imperfect mirrors in which the passengers can see themselves framed by dangling ticket stubs. Some are still multitasking, others just staring into space.